It’s come to the point of parody now that anyone caught criticizing Rodrigo Duterte’s brutal war on drugs is described as someone who supports drug crime. When the drug war’s death toll is brought up, the conversation inevitably descends into insinuations that you have forgotten about all the victims of the rapists and murderers hopped up on drugs who have gone on rampages throughout the Philippines, making all those Facebook commenters living in Riyadh and working at the Krusty Krab fear for their lives. Or something like that.

Even critics of the drug war concede that drug use is so life-destroying and conducive to crime that, while it may be that the war on drugs is being waged wrongly, we still need to take aggressive steps in stamping out the drug menace. This concession reflects just how deep anti-drug propaganda has seeped into public consciousness. But, once we look at the evidence, we will see that 1) the depiction of drug use as “one taste, forever hooked” is deeply flawed and 2) the link of drug use to violent crime is tenuous at best.

The government has been lying to us about drug use figures, but they have also been lying to us about the very nature of drug use. By looking at the scientific evidence and uncovering the untruths we have been sold about drugs, we also reveal the profound injustice of the drug war and how contradictory it is to any lasting solution.

What is addiction?

According to the US National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences.” While, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders describes “substance abuse disorder” as taking large doses of a substance longer than the intended period (e.g. Fentanyl use outside of prescription).

Substance abuse disorder is also characterized by a conscious desire by the user to cut down on use, though they spend more and more of their time to try and acquire the substance. Key to its definition, drug use is considered substance abuse disorder when it prevents someone from performing their major social roles due to activities associated with trying to acquire the substance or due to the use itself of the substance.

There is some evidence of genetic links that may predispose a person toward increased drug use, such as relatively higher tolerance to substances. And, on the matter of “addictive personalities,” although personality traits such as neuroticism and low conscientiousness may have some link to eventual drug use, there is no strong evidence that personality traits can be used to predict drug use.

How do drugs work?

The pleasurable effects of recreational drugs stem from how they trigger dopamine production in the brain. Dopamine is not in itself pleasurable, but it is involved in many neurological events that regulate emotion, motivation, and pleasure.

Duterte’s bête noire, shabu (or methamphetamine), also has other associated effects that contribute to its popularity such as: increased alertness and suppressed hunger. You can imagine why such a substance would be popular among people who need to be awake for long hours for work that pays them barely enough to eat. It is little surprise then that the vast majority of Duterte’s victims are poor. He himself has dismissed the drugs of the wealthy like coke and heroin as “not as destructive to the mind” as meth. And that is the issue at hand, isn’t it? Drugs are supposedly so bad that they destroy the mind. Duterte says that drug users are the “living dead.” We’re supposed to believe that drug users’ minds have been so thoroughly corrupted that killing them in drug operations isn’t a loss to the country.

This idea of zombie drug users has taken hold even in the minds of drug war critics, but there is practically no evidence that this is the case. While some drugs such as meth, ecstasy, and mainly the very much legal alcohol are neurotoxins, Yale University School of Medicine’s Sally Yates says,

Yes, addiction changes the brain but this does not doom people to use drugs forever. The most permanent change is memories.

Withdrawal from drug use may be harrowing as the body adapts to the abrupt loss of substance it had grown dependent on. But, some of its worst symptoms are the result of bringing back things that predate the drug use itself and may have even motivated drug use: mental illness is no longer self-medicated with the drug, chronic pain comes roaring back, and severe malnutrition is no longer hidden.

What causes drug addiction?

It may be self-evident that drug use causes drug addiction. One hit and you’re hooked for life. This image of the forbidden substance is illustrated by the classic experiment of making rats choose between a button that supplies them morphine and a button that releases food and water. This classic experiment’s result: the rats loved morphine so much that they kept pressing the morphine button until they died of starvation and overdose.

Conclusion: drugs are so bad that you get hooked on it until it kills you. So, our Dear President was right all along!

However, the psychologist Bruce Alexander found severe issues with this experimental design. Mainly, he asked, why didn’t the rats have anything else to do? They were locked up alone in cages and only had food or drugs. To challenge the classic wisdom, he created Rat Park.

In Rat Park, rats were no longer alone. Rats are deeply social animals. This is one of the reasons we use them as model animals, after all. Their behavior and brain structure are similar to humans in many important respects. In this environment, the rats were given the same choice: drugs or food. And, what Alexander found was that even if you force-fed rats morphine and even if they were undergoing withdrawal symptoms, they preferred the company of their other rats and they suffered their withdrawal symptoms together.

The skeptic might say, these are rats. What about people? Fortunately, or unfortunately, we have had a real-life analog of Rat Park.

During the Vietnam War, heroin was widely available to US servicemen. Up to 20% of them self-identified as addicted to heroin. And yet, 95% of these “addicts” went home without relapsing into drug use. This seems completely contradictory to the walking dead description Duterte had for drug addicts. So, how did this happen?

The treatment regimen for these servicemen focused on addressing the physical dependence in Vietnam. The only time they returned to the US was when they had lost the physical dependence on the drug. Leaving Vietnam removed the environmental context of their heroin use. They were able to reintegrate into their communities and they no longer had their surroundings reminding them of their drug habit.

Is addiction a disease?

The prevailing view of addiction is that it is indeed a disease. It is defined as a disorder by the DSM, after all. However, many scientists have come out to challenge this view. In the paper Addiction: Current Criticism of the Brain Disease Paradigm, Rachel Hammer and her co-authors wrote,

“…the lack of a molecular diagnosis is a point of criticism for opponents and a source of frustration for scientists.”

In other words, it is actually hard to pin down what addiction looks like from an objective biological standpoint. And, even if we do consider addiction as some kind of disease, it is actually a very treatable one. Most people who use drugs eventually quit.

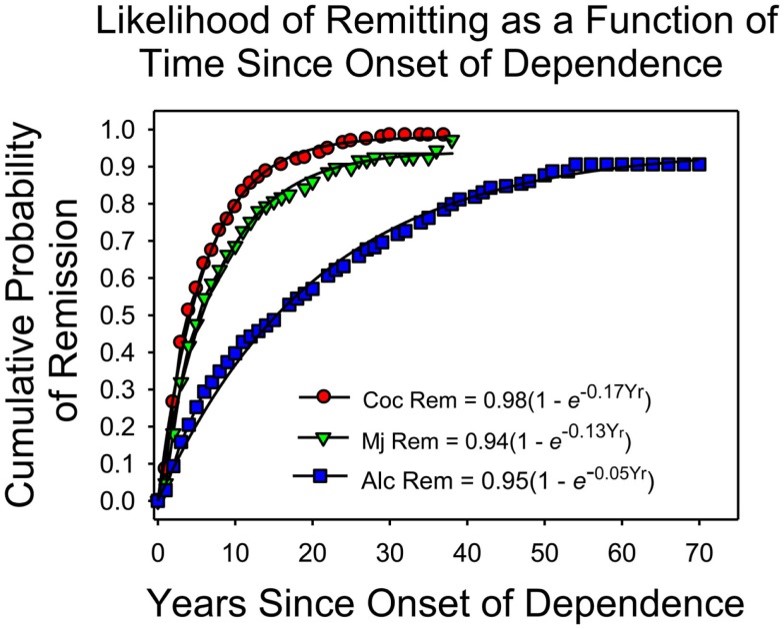

In the paper Addiction and Choice: Theory and New Data, Gene Heyman of Boston College collected data that showed that remission from drug addiction had extremely high rates for cocaine and marijuana. Contrast this to alcohol dependence, which, as you can see from the graph can reach an average of 20 years for just 50% of dependents to quit. We will learn more about this hypocritical attitude we have toward alcohol later.

Are addicts mindless slaves to drugs?

“Ang unang mawala dinha ang cognitive. Mokalit ug istorya, murag boang kay wala na lagi. No sense.” (The first to be gone is the cognitive. They talk suddenly like crazy persons because their cognitive sense is gone.)

Our President said this. And, I hope at this point you have been convinced that Duterte is no expert on drugs. I hope you are being slowly weaned away by the evidence from this notion that drugs are so especially life-destroying that they turn people into zombies focused only on feeding on more drugs. And since drugs are quite evidently possible to quit, perhaps we should start asking ourselves what is it about society that is driving so many people to take drugs in the first place. Because, it is not simply due to the alleged brain-meltingly addictive properties of drugs.

The neuroscientist Carl Hart conducted experiments on this very idea of the drug-addled meth fiend, this boogeyman so frequently paraded by Duterte and his disciples. Hart housed meth addicts in a hospital ward and gave them the option of taking pharmaceutical grade crystal meth doses throughout the day, or the delayed reward of collecting money by the end of the several week-long trial.

Every day and at different points of the day, Carl Hart would offer the study subjects: meth doses, $5 gift cards at the end of the trial, or $5 cash at the end of the trial. And, contrary to what we were supposed to believe from Duterte and other purveyors of the drug zombie myth, majority of the subjects chose money or vouchers.

In a variation of the study, Hart would up the dosage at levels unknown to the subjects. And, while increased levels of meth persuaded the subjects to start choosing meth again, the favorability of this choice disappeared with higher levels of cash/gift card offers.

Thus, Carl Hart was able to show that “addicts” are actually capable of rational decisions. It is just that the high drugs give is also something they consider. Whether they use meth to delay hunger, to stay alert for late night work, or to space out from the troubles of their lives, meth gives them something of value. And, if you offer them something of equal or greater value, they can rationally make that judgment, even it means delayed gratification.

Do drugs lead to crime?

Duterte ran on drugs and little else. There was the side narrative of fighting the oligarchs, and we heard people clearly unfamiliar with the word trying it out for the first time during the campaign period. Of course, Duterte himself comes from a political dynasty tied to various other oligarchs, including the Marcoses. It doesn’t get more oligarch-y than that. Today, nearly everything, from terrorism to human rights activism, has been linked to drugs and drug money by Duterte and his administration.

Despite the government’s own numbers saying that there were 1.7 million drug users in the country, Duterte has gradually inflated these figures up to the current 4 million figure. The basic implication Duterte and his followers make is that drugs users are rapist murderer fiends who will slash your face in their drug-addled haze. On that note, critics are enjoined to have a taste for themselves of what it means to be a victim of an addict since we are so inclined to defend them. But this basic implication of drugs ⇒ violent criminal does not stand up to even the most casual scrutiny. In Between Politics and Reason, Eric Goode of the Stony Brook University wrote,

“Even the fact that drugs and crime are frequently found together or correlated does not demonstrate their causal connection.”

This basic tenet of science may be too abstract, but it is critical to any drug enforcement policy. If drugs aren’t the cause of violent crime, maybe we should stop responding to it so… violently?

In the paper Dynamics of the Drug-Crime Relationship co-authored by Helene White

and Dennis Gorman, some of the findings they wrote would be completely alien to the common wisdom in Duterte’s administration. Their study found that most drug users never commit any crimes, except for the obvious crime of possession. And even for those involved in crime, it was not drug use that initially got them involved in crime.

And while the sha-boogeyman eternally haunts Duterte’s nightmares, it’s actually alcohol that is most associated to pharmacologically motivated crime. Because of what we know about the terrible results of Prohibition, nobody suggests banning alcohol. And yet, we are doing the exact same mistakes for other kinds of drugs. In the paper Psychoactive Substances and Violence, Jeffrey Roth wrote,

“Of all psychoactive substances, alcohol is the only one whose consumption has been shown to commonly increase aggression.”

Further, White and Gorman conclude that it is drug market forces that motivate drug-related crime. Since drugs are illegal, people in the world of drugs create their own shadow economy, complete with pseudo-police and pseudo-states to enforce, which lead to turf wars. Rather than drugs causing crime, it is the very illegality that is most to blame for the violence. But that is not even what drug war cheerleaders are most worried about. They incessantly point to the provably false link between drugs and non-organized crime.

It is also important to note at this point that as Duterte escalates law enforcement response to drug use, so too does the response of the drug market escalate. If the police can kill a mayor in custody, jail a senator with the collusion of convicts with little motivation to tell the truth, abduct a Korean national and murder him in the national police headquarters, execute people and plant drugs and guns without consequence, there is practically no incentive for drug users to ever cooperate. Your death warrant has already been signed. What is left for drug suspects when the cops are at their door but to try to escape by any means necessary?

What can we do?

While Duterte has openly mocked the idea of drug decriminalization and while its proponents may point to Portugal as a model of drug decriminalization. We must note that drug decriminalization will not address drug use. It may deescalate violence. It may kill the drug black market. It may decrease drug deaths. But, even Portugal’s experience shows drug use remained identical to neighboring countries.

The UK Home Office found that between the very strict drug laws of Japan and the lax rules of Portugal, “We did not in our fact-finding observe any obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country.” That is to say, Duterte’s tough on drugs stance actually does very little to address drug use. At that point, we might question the justification of the innocents murdered in the drug war as “collateral damage,” when the drug war itself does not even address the issue of drug use. If “drugs corrupting the youth” is Duterte’s motivation for the drug war, the evidence shows that he is not solving the problem in any meaningful way.

It is clear that while decriminalization is no silver bullet, neither is waging a protracted war against drugs. Our response to the drug problem must take into consideration why people go into drugs in the first place and how the criminalized supply of drugs subverts capitalism into a primitive form. There is no simple answer, but we need to have solutions that go beyond what has already taken the lives of thousands of Filipinos.

The war on drugs is not just ineffective, it is counter productive

The issue of drugs has been exaggerated in many respects and ineffectively responded to. What the evidence shows is that people resort to drugs as a rational response to personal and social problems, such as poverty, hunger, and mental illness. The trouble is, these are not problems you can shoot your way out of. They are not issues you can solve in three to six months. But, then again, neither was the war on drugs.

Rather than address the social problem of drugs, focusing on the illegality of drugs has made users vulnerable to black market forces as they lose the protection of the state. Worse, they become victims of the state itself as it tries to fight a war that has been failed by more capable states. Compounding this, drug users are vilified by their fellow citizens, leaving them with little else to turn to except fall deeper into the very social isolation that led them to resort to drugs in the first place.

Drug war. What is it good for? The answer is increasingly looking out to be: absolutely nothing.

Addendum

The research shown here is not meant to discount the personal experiences of people with drug-related crime. Rather, the studies here give a wider view of how much blame we should levy on drug use, which is: not that much. The strength of the research by scientists such as Carl Hart is precisely rooted in the controlled environments they create in order to isolate variables and to minimize unforeseen effects of extraneous events such as: the influence of other people and material circumstances of the subjects. These studies allow us to focus on matters that can actually address the root causes of crimes.

Once we have realized that drug use is usually caused by social problems, we can focus on creating programs that allow drug users to reintegrate into society and find productive livelihoods in the formal economy. We have to address why people use drugs, and why people enter the drug black market. As long as we leave people in the margins, they will fight to stay alive, even through illegal means.

The plural of anecdote is not data and Facebook comments do not carry more weight, however many, than a controlled study. For every drug user that rapes or murders a neighbor, there are many more who have done the same and didn’t use drugs, or were drunk from alcohol, which research shows has a stronger link to violent behavior. Singling out all drug users for the crimes committed by some is not very different from targeting all undocumented immigrants in the United States because of their perceived criminal nature.

We are living in a dark chapter in Philippine history. There is an active democide happening at this very moment. Duterte has already functionally dehumanized drug users in the country. Thousands, if not millions, celebrate the murder of Filipinos every night in the streets. But, if we continue to shed light on the great injustice of the drug war, perhaps we can at least make it a brief chapter.

Thank you for a very well expounded article. It’s hard to go against the tide Esp if you are going against rampant misinformation. I have been mocked by Duterte fanatics when I brought up the crime-alcohol link, but these data’s have been there for a long time. it’s just frustrating that our education system is lagging behind in so many departments. But articles like these are starting to break thru the fog. Thank you again.?

Congratulations. This is well-researched and clearly presented.Unfortunately, supporters of the president are very unlikely to give this piece the attention it deserves.