Let’s get back to basics. The following is a case against a cosmological argument for the existence of God.

Intelligent (not “folk”) Christians will repeatedly tell you that faith and reason are both used in their theologies. Unlike the laity and the unwashed masses, they don’t rely completely on faith, or belief without evidence. Indeed, the Christian religion in its many forms has a long history of logical attempts, from Aquinas to Calvin, at trying to prove the existence of God and the plausibility of their doctrines. This is perhaps due to the fact that certain intellectuals in each tradition simply cannot reconcile their rationality with their religion’s doctrines.

Through tireless philosophical refinement of initially primitive and unimpressive doctrines such as the Genesis myth, we get sophisticated logical arguments such as Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways. Seeing these attempts at logical proof, though, I am personally baffled by the intelligent theist’s recourse to faith. If God is provable through reason, of what use is faith? If faith is sufficient, why use imperfect human reason?

Philosophical arguments for God take various forms, such as the cosmological, ontological, and teleological arguments. There are, of course, many criticisms against most, if not all, of these. The cosmological (first cause) and teleological (purposeful design) arguments are empirical arguments, taking the world as it is and reasoning that there must have been a Creator.

One of the most interesting of these arguments, for me, is the Kalam cosmological argument. Unlike most arguments for God, it intends to at least be scientific in its attempt at proving that a personal God exists. Through its most vocal proponent, theologian William Lane Craig, the Kalam is used to argue that the universe must have had a cause. Formally stated, the Kalam appears as such:

(1) Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

(2) The universe began to exist.

(3) The universe has a cause.

Everything that begins to exist has a cause

Premise (1) asserts that everything that begins to exist has a cause. This statement evades criticisms such as those that Bertrand Russell put forward against Aquinas such as, “Who made God?” Since the Kalam argument states that everything that begins to exist has a cause, God, who is eternal and never began to exist, does not have a cause.

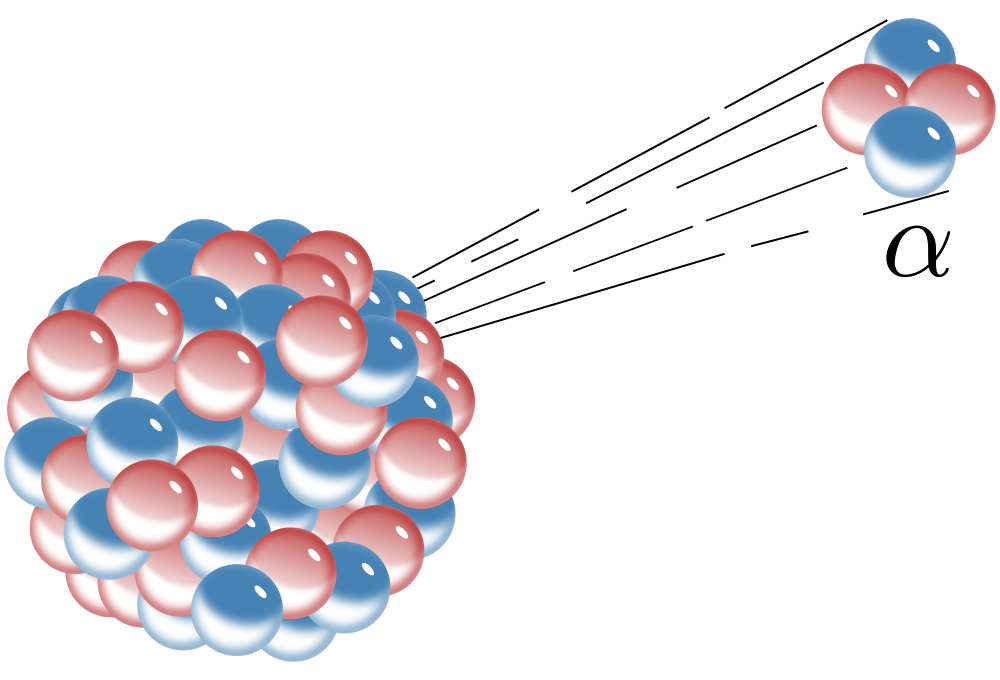

Physicists such as Victor Stenger have argued that not everything that begins to exist has a cause. When an electron increases in energy to an excited state and returns to its ground state, a photon appears. This appearance of the photon occurs spontaneously and is not a deterministic consequence. That is to say, in Stenger’s words, it is “without cause.” The same is true for the radioactive decay of the atomic nucleus. We can know the probability of decay but it is impossible to say exactly when the decay will occur.

William Lane Craig readily counters this by saying that that is not true causeless existence since nature, which God presumably made, is necessary for such events. However, Craig must now accept that probabilistic causes, if they are “causes” at all, are possible mechanisms for the beginning of the universe. This severely weakens the notion that a personal God predetermined the moment of creation with a purpose.

However, even accepting Premise (1) as true, we can move forward and still see that the Kalam argument ultimately fails in its misuse of time.

The universe began to exist

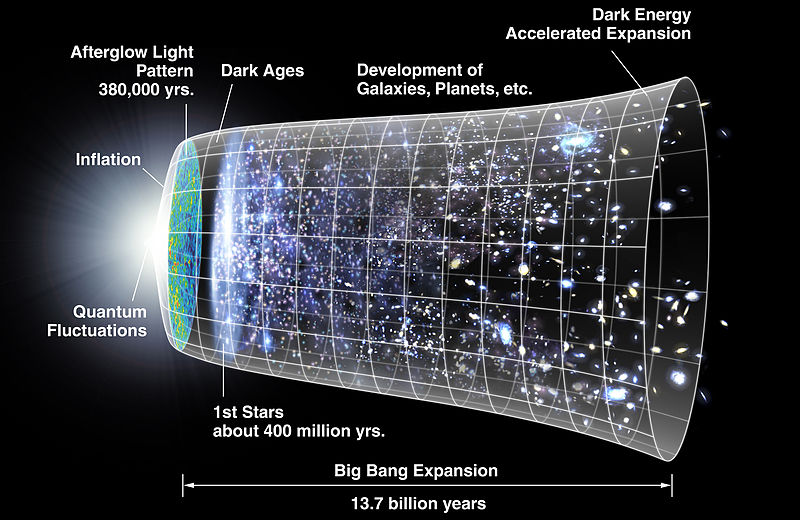

The discovery of the Big Bang model of the origin of the universe was very popular among theists. The Big Bang, they suggest, is proof positive that the universe began to exist. When Georges Lemaître first proposed the model, Pope Pius XII saw this as scientific evidence for creation, “it seems that science of today, by going back in one leap millions of centuries, has succeeded in being witness to that primordial Fiat Lux when, out of nothing, there burst forth with matter a sea of light and radiation, while the particles of chemical elements split and reunited in millions of galaxies.”

Theologians and apologists such as Craig and Dinesh D’Souza find that since the universe as we know it began 13.7 billion years ago in the Big Bang, then the universe began to exist and it had a cause for its existence. Craig, in the Islamic tradition of the Kalam, suggests that since the universe began to exist 13.7 billion years ago, then there must have been a “particularizer” to decide to begin the universe at that moment and not a moment before. And since this particularizer has the capability to decide and distinguish between moments, then this must be a personal kind of God with a mind analogous to ours (therefore not the deist’s God).

Remember, though, that Craig can no longer require this decision to create the universe to be particularized by a personal God since he must allow that probabilistic causes are possible causes for the universe. The mechanical circumstances necessary for atomic decay are all already in place, even though the effect of a decayed nucleus is delayed. The nucleus could decay in 2 seconds, it could decay in 100 billion years. This defeats the necessity of a personal God deciding to create the universe 13.7 billion years ago and not 12 or 20.

As James Still has seen, Craig’s view of time results in severe problems for the Kalam. It seems that in his view, time exists not in the physicists’ definition of time. Physicists use time in the relational view, where time exists relative to bodies in motion, like ticking clocks. This is integral to Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity, where the experience of time changes depending on velocity and the presence of mass. This effect has been confirmed and global positioning systems would fail without the corrections predicted by relativity. More importantly, general relativity shows that, if the universe did begin to exist, time itself began along with space, energy, and matter.

It makes no sense in the relational view of time to suggest that the universe could have had begun a moment before since there were no moments “before” the Big Bang, which is when time started ticking. Therefore, Craig seems to see time as absolute in his metaphysics. Personally, his view makes no sense to me. Perhaps he believes that events can be absolutely simultaneous regardless of frame of reference, which goes against special relativity. At the very least, we know that Craig clearly does not mean “time” in the way it is used by scientists.

It has been suggested that it is possible that the universe has simply always existed—a “brute fact,” in Russell’s words. This would remove any need for a creator since the universe did not “begin to exist.” However, Craig counters this by supporting Premise (2) with the following argument:

(4) An actual infinite cannot exist.

(5) An infinite temporal regress of events is an actual infinite.

(6) Therefore, an infinite temporal regress of events cannot exist.

Through this argument, Craig contends that it is impossible for the universe to have always existed since this would require an infinite temporal regress of events. Craig uses the example of Hilbert’s Grand Hotel to show that an actually real infinite would lead to absurdities.

Briefly, David Hilbert’s paradox of the grand hotel shows that if you have a hotel with an infinite number of rooms, it can accommodate an infinite number of guests. It should then be full after checking in an infinite number of guests. But, if another infinite number of guests should wish to stay in the hotel, one would only need to move the first set of guests to odd numbered rooms and the second group into even numbered rooms. You have now accommodated another infinite number of people in a supposedly full hotel. Craig argues that since this is a counter-intuitive result, then an actual infinite must be impossible.

It is important to note, however, that counter-intuitive results show up in science all the time. The greatest example of this is the discovery of wave-particle duality. A particle can be at many places at the same time. A particle can have many states at the same time. It is therefore not true that counter-intuitive results are necessarily impossible. However, we need not reject Craig’s use of Hilbert’s Hotel to see that Premise (2) in the Kalam is problematic.

Contrary to how Craig views the Big Bang model, the standard model of cosmology does not necessarily see the universe as beginning from a single infinitely dense point—a singularity. This prediction that the universe began as a singularity, via the Penrose-Hawking theorems, was because the Big Bang was erroneously viewed purely through the lens of General Relativity. Both Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking would later revise their position. Taking into account the physics of quantum mechanics, which would dominate at the extremely small scales of the earliest moments of the Big Bang, Hawking says, “There was in fact no singularity at the beginning of the universe.”

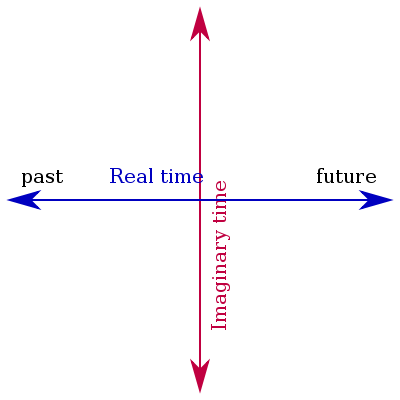

It is completely possible, as Hawking suggests in A Brief History of Time, that the universe has no boundary in time. This means that t = 0 (where t = time) is merely in the middle of a continuous line of imaginary time (a concept necessary to describe quantum tunneling), like how the South Pole is not the end of the Earth, but just another point along the longitudes. Trace the longitude going through the poles of the Earth and you get a finite but unbounded geometry—a great circle; the same could be true for four dimensional space-time. It therefore stands to reason that time need not have a beginning, as a singularity would suggest.

In any case, singularity or no singularity, the scientific relational view of time avoids the problem of an infinite addition of events leading up to today because, although the age of the universe is finite, it is also true that the universe is eternal and has always existed. There has never been a time when there was no universe.

The universe has a cause

Craig asserts through an absolute view of time that actual infinities cannot exist. This would also apply to God. God cannot have existed through an actual infinite addition of events going back to nowhere. To get around this, theologians can assert that God is eternal not in the infinite number of events sense but because he is timeless. Unfortunately for the theist, since God is timeless, there would also never have been a time when God did not create the universe. The eternal universe would also be timeless in the same sense.

If Craig is to retain his absolute view of time, he must also reject the impossible timelessness of God. God must have begun to exist and himself have a cause. We can repeat Bertrand Russell’s challenge, “Who made God?” If Craig is to accept the physicists’ relational view of time, he must also accept that the universe is “eternal” in the same sense that God is eternal. Premise (2) fails and God is then an unnecessary explanation for the universe’s existence.

As Paul Draper notes, another problem with the Kalam cosmological argument is that it equivocates two senses of the phrase “begin to exist.” The strength of the Kalam cosmological argument is that it purports to be a proof of God from the evidence. It uses inductive reasoning to show that since everything begins to exist from causes, then the universe must also have begun to exist from a cause. However, the things we see to begin to exist begin in time. The universe, if it began to exist, began with time 13.7 billion years ago. We have no experience, no valid intuition, of things, let alone universes, beginning with time. Craig therefore commits the fallacy of equivocation in reasoning from the example of ordinary objects that the universe must also have a cause. Even if we accept Premises (1) and (2), the conclusion of the Kalam cosmological argument remains invalid. The eternal universe remains a brute fact.

TL;DR

The Kalam cosmological argument was a very strong case for the existence of not just a supernatural creator, but a personal one with a mind and thoughts. Because of the supposed impossibility of infinities in the real world, there is indeed a real problem for the naturalistic existence of the universe.

All of these arguments, however, have been fatally challenged by what we know today about the universe. The necessity of a personal creator is refuted by the existence of natural mechanisms for probabilistic causes. This means that naturalistic causes need not have their effects occur immediately after. The eternity of the universe is also supported by the dependence of time on space. In other words, without the universe, there was no time. Without time outside the universe, there was never a time without a universe. Hence, the universe has always existed and a creator is unnecessary to explain its existence.

It was perhaps impossible to have been an intellectually satisfied atheist until the discovery of relativity and quantum mechanics. The refutation of the Kalam heavily depends on the evidence that supports these theories. This did not have to be how nature is. As we learn more about the peculiarities of the universe, the God-shaped hole at the end of the universe is all but plugged.

All images are public domain except image on quantum tunneling by Jean-Christoph Benoist. Licensed under Creative Commons.

Prof Vilenkin said: “It is said that an argument is what convinces reasonable men and a proof is what it takes to convince even an unreasonable man. With the proof now in place, cosmologists can no longer hide behind the possibility of a past-eternal universe. There is no escape, they have to face the problem of a cosmic beginning (Many Worlds in One [New York: Hill and Wang, 2006], p.176).

Here is a video of Alexander Vilenkin explaining the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin Theorem (BGV). It doesnt depend on the standard model of Einstein’s General Relativity. He also addresses criticisms of his theorem.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=WOyQFkB1AGM

The idea that the universe is eternal in the past is dead. To continue to believe that in this day is to believe in the carcass of a dead superstition. That atheists still persist in believing this just proves that freethinkers are just incapable of giving up their most cherished superstitions.

1. Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

2. The photon began to exist.

3. Therefore, the photon has a cause.

Do photons just pop into existence? No.

What causes photons to exist? The excitation of electrons from one state to another.

But the great physicist Victor Stenger says photons just pop into existence without a cause. And Garrick believes him.

There is a thin line between good science and bad superstition, and Stenger just crossed it. A scientist however cannot exactly be blamed for doing bad philosophy. But there’s no justifying a philosopher for believing a scientist who does bad philosophy.

As a website said, “When physicists add “infinity” and “nothingness” to their conclusions, they are not anymore doing physics since the notions “infinity” and “nothingness” in their true sense are not empirical and can never be subjected to the scientific method. Rather, they are purely philosophical notions, hence, allowing us to subject them into a philosophical critique.”

http://catholicposition.blogspot.com/2013/11/can-…

Arguments for the existence of God are philosophical, especially of St. Thomas of Aquinas and also of Kalam. If you really want to fully refute these, then you should argue philosophically also.

Lawrence Krauss has excellent theories in this areas…about says it all!

Here’s an excellent point for point refutation of Garrick Bercero’s “The Eternal Universe”: The Eternal Universe and Science

Any say Garrick?

If your familiar with Stephen Hawking's book. The Grand Design, he and his co-author Leonard Mlodinow thought that the "First Cause" theory is not applicable to the Big Bang model, everything can be created from nothing. They proposed that with the Big Bang, everything was created, matter, space and energy and also time begins to flow. Time doesn't exist before the Big Bang thus no one including god has the time to think of a plan to create a universe…

1. From James Sinclair, "One can avoid this, as the Aguirre-Gratton model does, by reversing the arrow of time at the boundary (as Vilenkin told AA). But if you do this, then the mirror universe on the other side of the BVG boundary in no sense represents a past out of which our current universe evolved. Thus our universe would begin-to-exist, should the A-theory of time be true."

James also points out, "the Aguirre-Gratton model is not even suggested by its authors to be a model of our universe. Rather, they hope that it can serve as a springboard for the birth of our universe through some other physical process (some of which they briefly mention in their academic paper)".

Read more: http://www.reasonablefaith.org/current-cosmology-…

2. What Craig means by "topologically prior" can be understood by taking it to mean "causally prior", that is, the story of the evolution of the universe includes the state that is prior to the origination of time (and by implication, the universe).

However, I too am having problems with this as it strikes me as being circular.

I don’t mean that our universe does not have a greater than zero expansion rate. It appears to have such an expansion rate. Our universe, as Vilenkin proposes, tunneled out of a spaceless/timeless natural plane (which I call the UGM). This plane is what is not affected by the BGV, not just universes such as those proposed by Hawking, Carroll, or Aguirre (which all expand but still are not subject to the BGV).

I never meant to imply that you believed the universe isn't expanding.

Carry on. 🙂

Garrick,

The problem I see is that your UGM has features for which you provide no evidence; you say this UGM is "ontologically non-contingent" and has universe-making properties that are just inexplicable (which conveniently obviates certain questions about it –like why it won't create pink bunnies). You imply it's a brute fact, and while I'm not ruling out the fact that, at least in principle, it can be, you nevertheless give no reasons to support this.

The Cosmological Argument, it should be said, doesn't merely try to establish a cause that relatively differs in degree from other causes of which we can be familiar. Nor does it attempt to give an explanation for phenomena that's currently beyond science's reach.

The Cosmological Argument, as traditionally understood, evolved from attempts to demonstrate the need for causality to be undergirded by certain metaphysical preconditions. Therefore, what's being postulated by the argument is that which in principle has to exist, and that which in principle cannot be said to have had a cause. (Of course, other properties can and have been inferred, but let's overlook these for now.)

Now, it seems to me, what you're doing is you're saying, without evidence, that the UGM is it, while parrying putatively meaningful philosophical questions about its nature by saying 'it's just that way'. I hope you understand why this all seems ad hoc. (I used 'post hoc' previously, but 'ad hoc' is in fact the better word)

In my discussions with _XIII_, you’ll see that the properties of the UGM are not ad hoc and are supported by cosmological models of spaceless/timeless quantum mechanics. These stem from formulas that were created to solve other problems but turned out to show more fundamental properties in nature. The UGM is not a magic black box that makes any random thing and the physics supports this. The UGM creates zero total energy closed universes and the formalism of quantum gravity bears this out. It is arguably ontologically non-contingent because it is timeless and spaceless—eternal. It almost makes no sense to explain why there can be “nothing” and to ask how a lack of space and a lack of time can “begin to exist.” It might not be necessary, but, like Swinburne, I don’t think even God is logically necessary.

I think cosmological arguments tend to be question begging as they presume that everything has a cause or everything has an explanation. This already quite a loaded assumption that is tailor fit for gods. I said this elsewhere regarding the Leibnizian cosmological argument.

The Kalam’s intuition about causes is highly questionable. As I say in my piece, it conflates completely different meanings of “begin to exist.” In fact, it can be considered that nothing begins to exist in the Kalam’s sense since all matter and energy in our universe had the universe as their causal condition. Every “thing” that there is now has existed since the universe began. It’s just that the matter has come to be configured in such a way that they make things we conceive of as human beings and tables. If this is so then, as Jonathan Pearce shows, the Kalam would look like:

1. Everything that begins to exist has the universe as its cause.

2. The universe began to exist.

3. The universe had the universe as its cause.

The Kalam’s “everything” is actually just the same stuff that makes the universe up and becomes completely circular if we take into account the fact that nothing begins to exist in the universe apart from the causal conditions of the universe.

1. The universe that begins to exist has a cause for its existence.

2. The universe began to exist.

3. The universe has a cause for its existence.

The Kalam uses one example (our universe) to assume an all-pervading metaphysical rule.

Even then, our universe having a cause, given quantum tunneling/quantum gravity models, doesn’t even prove the supernatural cause desired by Craig.

Timelessness doesn't in any way entail ontological non-contingency. If you think it does, then lay out your case. The CA –at least classical versions– as you undoubtedly are aware, doesn't postulate timelessness as one reason for concluding the ultimate cause must be uncaused.

And the cosmological argument doesn't beg the question about contingent things having a reason for their existence –that part is presumed to be true because it is squarely supported by the evidence. What is in fact question-begging is your presumption of this premise to be "question-begging" without argumentative support. Now, you might say Quantum Mechanics shows that not everything has a cause, but, if you remember, this objection has been dealt with.

You say elsewhere there's no reason to think the Leibnizian CA is sound because it's "question-begging" as it presumes the existence of a necessary being; "the principle cannot be true if necessary beings don't exist"; "the principle can only be true if we already assume that at least one necessary being exists" But this statement is itself question-begging because the "weak form" of the PSR doesn't presume a necessary being exists, it concludes a necessary being must exist, precisely to escape an infinite ontological regress. You therefore beg the question about it's conclusion being unsound, again, without valid argumentative support.

Whether you're aware, you even imply classical CA's are sound by making the UGM out to be this "ontologically non-contingent" thing. The difference I see is that while the classical CA's use strict metaphysical demonstrations to show why something of this nature must be at the end of the line, you –assuming I'm heretofore successful in the case I've laid out– assert the UGM is it.

Now for all we know, you may be right and the UGM is in fact it. But you've skipped a lot of steps, it seems to me, in getting to your conclusions –at least for the ontology part. And the end result, to my mind, seems more improbable for the reasons I've previously given.

Neither did I suggest that timelessness did solely imply non-contingency. But the spaceless, timeless UGM has no stuff to begin existing at all.I think it's quite unfair to paint my complaint against cosmological arguments as “without argumentative support” when I lay this out in other threads. I will repeat it here. Even weak variants of the PSR can only be true, in that all beings will have an explanation, only if at least one necessary being exists. This is because, in a possible world with no necessary concrete beings, the PSR cannot be true since an infinite parade of contingent beings cannot sufficiently explain each other. Therefore, the assumption of the weak PSR already assumes the conclusion that at least one necessary being exists. The weak PSR may not explicitly assume it, but it definitely requires such an assumption to be true.

If it has "no stuff" at all, then how is it that it creates particular kinds of "stuff" and not the patently absurd ones of which we spoke. See, it has "stuff", and it's the kind of "stuff" that science can't in principle say doesn't exist on account of its inability to observe it. And if it's stuff that's "spaceless and timeless" then it's stuff that still cannot be said to be in principle ontologically non-contingent by virtue of just these features.

I'm sorry for not being clear, I wasn't saying the contentions you raise against the CA –particularly, the Kalam– are without merit, I was saying the contentions you raise against the PSR are. And I'm afraid you're doing it again by making the conclusion its premise; it's not that "all beings will have an explanation, only if at least one necessary being exists." but that, since, so far as we know, all beings or existents have an explanation, a necessary being must therefore exist.

Suppose you say to a creationist that evolution is supported by the fossil record, and he responds by saying you're begging the question because you need evolution to be true for it to be supported by the fossil record. You would respond firstly with an open-mouthed expression of incredulity, and then you'll say that rather than providing bad grounds for believing in evolution, the fossil record furnishes us with the opposite.

In other words, you require the support of the fossil record for evolution to be true, and not the truth of evolution for the fossil record to support it. Likewise, we require beings or existents to have explanations to support the notion of a necessary being, and not a necessary being to support the notion that beings or existents have an explanation.

What the creationist could say is that the fossil record doesn't support evolution (of course, he would be wrong), and what you, in turn, could say here is that beings or existents, or, maybe, some beings or existents, don't have explanations, but, as you undoubtedly must be aware, without any supporting argument, that would just be to beg the question.

(I'm sorry! This will be my final post on this seeing as you must be exhausted by having to respond to all these lengthy arguments. I applaud you for the remarkable amount of research you've put into this. 🙂 )

I think this is where I must resign to ignorance. The spaceless, timeless phase from which Vilenkin's or Krauss' universe models tunnel from or fluctuate from, or via however mechanism, is simply is devoid of any material. No particles, no waves, no nothing. I don't know why quantum mechanics should even still operate in such a condition, but the math checks out, at least for Vilenkin and Krauss.

What I'm showing with my example of a possible world with no necessary beings is to illustrate that the PSR is only effective if it assumes that a necessary being exists. Sorry if I keep repeating myself, because it seems rather self-evident to me. (I understand that it's rarely ever the same for everyone. 😛 ) For example, in a possible world that only has contingent beings, let's go one by one and explain each being. At some point, there will come a time where an approach towards an infinite regress of explanations occurs, or a complete cessation of explanations. In a possible world such as this, the PSR would be false (since not everything has a sufficient reason). If we were to live in a possible world with a necessary being, then the PSR would be true. Therefore, the PSR's truth value, our premise, is completely dependent on what kind of world we find ourselves in.

I think the analogy with the fossil record fails because we are certain that the fossil record exists (if we are certain about anything at all.) The fossil record is not a metaphysical principle that guides us in proving evolution. It is an a posteriori finding of paleontology. It counts as evidence for evolution. It does not prove evolution; it makes it more likely. It could be the case that the fossil record will not validate evolution. Even to this day, the fossil record could eventually show that evolution was a very effective, but nonetheless illusory, model. I doubt it, but it's not beyond possibility. Science is provisional, after all.

However, in the case of the PSR, it is our guiding principle. We are not certain that it is true because of evidence—we assume it is true. (As I've explained before, we've only ever found contingent beings explaining other contingent beings, never necessary beings explaining contingent beings.) As Leibniz's cosmological argument shows, there is no way at all for a true PSR to lead to an invalidation of the 'necessary being' conclusion. The PSR is not evidence for a necessary being, it is our axiom for finding the necessary being.

I think assuming the PSR is like assuming metaphysical naturalism. If this is assumed, then, necessarily, no gods exist.

Consider this syllogism:

(1) Everything that exists is natural

(2) God is not natural.

(3) Therefore, God does not exist.

Premise (1) is not evidence for no god; when assumed axiomatically, metaphysical naturalism is a principle that will always certainly result in a 'no god' conclusion. Now, a naturalist could say that certain things count as evidence for premise (1) (just like certain things could make the PSR more likely), but I don't think it could ever be axiomatically true.

In any case, I truly do appreciate the time you've given me. I've explored so many ideas you've clarified that I will probably dwell on for an infinite temporal succession of events.

@D.Gently

D.Gently: "What it does is put a 'limit' specifically (but not limited) to inflation, or a series of inflations, for the past direction."

That, however, is precisely the reason the BGV Theorem implies an absolute beginning (since the expansion cannot be past-eternal). This is why virtually all the exceptions to the BGV Theorem posit an average expansion rate ≤0. Garrick's UGM, for example, is completely static (it's expansion rate is not greater than zero) which is how he proposes it evade the implications of the BGV Theorem.

The problem is that these exceptions are universally plagued with intractable problems such that they hardly furnish us with proven alternatives to the implications of the BGV Theorem.

D.Gently: "I repeat Vilenkin's subsequent clarification: 'the words “absolute beginning” do raise some red flags'; (Does your theorem prove that the universe must have had a beginning?) 'No.'"

This is a bit misleading.

Vilenkin's reply, when asked directly what were the implications of the theorem, was that the simple answer was "yes" but that if you were willing to get into subtleties, the answer would be "no, but". There are indeed ways to circumvent the universe's having a beginning as I've always conceded from the beginning.

This is why Craig actually devotes several pages discussing these exceptions to the theorem in his article in the Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology.

Garrick: "Again, to clarify what all these scientists are saying, Vilenkin and Guth included, our universe is subject to the BGV theorem, the non-expanding era of space-less and timeless nature is NOT."

The problem with your UGM is that it's incoherent.

The Laws of Physics merely true propositions that describe how the universe operates and propositions have no causal powers. To illustrate, take Newton's Law of Universal Gravity and let's call it G: "that every point mass in the universe attracts every other point mass with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them".

Now, does G, a proposition that describes how gravity operates, cause the Earth to pull at the moon? No, it does not. What it does is describe the reason why the Earth pulls at the moon (that reason being gravity). It is not the proposition G that causes the pulling motion but gravity.

Even if we were to concede that your proposed UGM is Platonic, it still wouldn't solve this problem of causal inefficacy.

"The problem is that these exceptions are universally plagued with intractable problems such that they hardly furnish us with proven alternatives to the implications of the BGV Theorem."

Problems such as?

The UGM is not even an exception to the BGV theorem. It was never made to describe the UGM since it is not a universe. It is not a space-time continuum. It is the spaceless/timeless ontological prior of our universe, and perhaps of many other universes.

I'm not saying, nor is Krauss or Hawking saying, that the laws of physics, being propositions or ideas in scientists' heads, are themselves causally effective. I'm saying that "nothing" itself, that is the very physical absence of space and time, still maintains properties and tendencies that lawfully behave according to the uncertainty principle. The very fabric of nature has properties beyond space and/or time. That's why physical nothing (no space or time) is still "something", according to quantum mechanics (which, again, can operate even outside of space and/or time). This did not have to be the case. It could very well have been that quantum mechanics was found to require space to operate. But that is not what the theories bring to bear.

Cyclic models have an entropy problem, for example, while static models that give rise to the universe via quantum fluctuations are themselves metastable and thus past-finite. On a side note, this quasi-static metastable quantum vacuum (with an expansion rate of zero) is really quite similar to your UGM with the important distinction that it's still spatio-temporal.

And how exactly would this "nothing" (your UGM), that is timeless and spaceless, have causal powers anyway?

Quantum Mechanics breaks down past the singularity for the very simple reason that the realm wherein Quantum Mechanics operates ceases to exist (there being no space nor time). You are essentially redefining what Quantum Mechanics is if you're proposing it can operate timelessly and spacelessly.

The UGM you are proposing is completely ad hoc (that is, it's arbitrary in it's properties). Krauss' nothing is not nothing, as you yourself admit, and yet you keep extrapolating it past the singularity when Krauss' nothing presupposes space and time.

None of the models I've put forward, Hartle-Hawking, Aguirre-Gratton, or Carroll-Chen, are cyclic. The HH model has a universe with no boundary in time, no true beginning in time (as in the great circle analogy in my piece). The latter two examples are biverses, which mean that the universes are momentarily static at an arbitrary point called t = 0 then inflate at opposite time directions. They are also not quantum fluctuation models, rather they are quantum tunneling models. All three models are eternal universes. All three of these models have no singularity, all three not refuted by BGV. Indeed, a full picture of the Big Bang that includes quantum gravity is expected to not have any singularities.

There's a very big difference between quantum mechanics being unable to describe a singularity and "ceases to exist" past a singularity. This latter assertion is completely unsound. I am not redefining QM at all because the formulas used to prove known mechanisms such as particle-antiparticle annihilation are the same formulas used to show that QM operates outside of space and time. There is nothing ad hoc about any of this.

The spatio-temporalness of models such as Tryon's are problematic because of finite space. The independence of physical nothingness on space-time makes ALL the difference. It's like saying rocks are similar to bread with the important distinction that they are made of completely different atoms.

The causal powers of the UGM stem from the fabric of nature itself being shown through quantum mechanics as being subject to the uncertainty principle. This is highly counter-intuitive, but as I've said multiple times, our intuitions cannot dictate nature. Incredulity at the possibility of potentialities in spaceless/timeless nature is not an argument.

The UGM's properties are not arbitrary since its properties were not finely-tuned to give out a desired result. As I said, nature did not have to be this way, that it can be described by the uncertainty principle even in the absence of space and time.

Krauss' nothing does not presuppose space or time. Maybe you mean space and time in some non-scientific context.

"The lesson is clear: quantum gravity not only appears to allow universes to be created from nothing—meaning, in this case, I emphasize the absence of space and time—it may require them. "Nothing"—in this case no space, no time, no anything!—is unstable.

Moreover, the general characteristics of such a universe, if it lasts a long time, would be expected to be those we observe in our universe today." —Lawrence Krauss, A Universe from Nothing

XIII: 'This is a bit misleading. Vilenkin's reply, when asked directly what were the implications of the theorem, was that the simple answer was "yes" but that if you were willing to get into subtleties, the answer would be "no, but".'

No, not in the slightest misleading. For one, I gave a link and reference to the complete statement by Vilenkin, and second, Garrick actually provided the whole quote beforehand—after which one would find my shortened "No" quote (together with my suggestion of thinking of the BGV as pertaining more to the expansion or expanding regions). Here it is again, in full this time:

Stenger: 'Does your theorem prove that the universe must have had a beginning?'

Vilenkin: 'No.' [As in No, the theorem does not prove the universe must have had a beginning.] But it proves that the expansion of the universe must have had a beginning.'

Your contention has always been that the BGV proved the universe must have had an absolute beginning. If there 's any misleading being done, intentional or otherwise, it's your selective quotes and your continued refusal to even acknowledge what has been said in the paper itself, clarifications by its authors, and summaries given by the other competent physicists in the field..

You really need to move on from the BGV (your misuse and misunderstanding of it) as it is clear Garrick's UGM occupies a different realm. Beyond the expanding region of spacetime of the initial inflation where the BGV ends ('What can lie beyond this boundary?') is, I think, more spacetime for you to traverse, alongside a whole host of competing (scientific) accounts*—before the UGM is in sight.

(* Perhaps here, instead of the BGV, you can make use of one of Vilenkins more recent papers, co-authored with Audrey Mithani, in which they consider cyclic evolution and the emergent universe models and come out with the same conclusion, the universe is probably past-incomplete: Did the universe have a beginning?, http://arxiv.org/abs/1204.4658.)

@d.gently

I never denied that Garrick's UGM doesn't evade the BGV Theorem. I keep repeating myself. Remember, I said that universes with an average expansion rate greater than zero must have had a beginning in the finite past. This is precisely what Vilenkin says that the theorem proves that the expansion of the universe must have had a beginning.

This of course means that universes that do not have an expansion rate that is greater than zero aren't affected by the BGV Theorem. I have been clear about this from the very beginning so any accusation of misleading is grossly inappropriate.

XIII: ‘I keep repeating myself.’

So must I, it seems.

XIII: ‘Remember, I said that universes with an average expansion rate greater than zero must have had a beginning in the finite past. This is precisely what Vilenkin says that the theorem proves that the expansion of the universe must have had a beginning.’

Except that's not exactly what you’ve been saying. ‘[T]he theorem shows that any universe with an expansion rate greater than zero must have had an absolute beginning … The problem is that our universe does have an expansion rate greater than zero and that means that the universe must have had an absolute beginning.’ I’m sure, or would hope that, you agree that it is critical to note the massive difference between the paper's author saying the theorem only proves a past boundary to the expansion of the universe and you (or Craig) saying the theorem proves the absolute beginning of the universe. The two statements aren’t interchangeable, but that is exactly what you are attempting to do here.

XIII: ‘This is precisely what Vilenkin says that the theorem proves that the expansion of the universe must have had a beginning.’

Exactly … and that when asked if he thought the theorem proved the absolute beginning of the universe, the answer was ‘No.’ This stands in direct opposition to what you are—or have been—insisting that yes, the theorem proves an absolute beginning to the universe.

XIII: ‘This of course means that universes that do not have an expansion rate that is greater than zero aren't affected by the BGV Theorem.’

This is inaccurate; the universes in the three models that Garrick already mentioned are all expanding and yet evade the BGV. (Aguirre, http://bit.ly/NWi4Xr: 'What all of their theorems do are (a) write out a set of conditions which they consider to correspond to eternal inflation, then (b) show that the region in which these conditions hold is geodesically incomplete. This would indeed be consistent with eternal inflation “emerging from a primordial singularity”, but it is also consistent with eternal inflation just being grafted onto some spacetime region that is not eternally inflating by their definition.')

XIII: ‘I have been clear about this from the very beginning so any accusation of misleading is grossly inappropriate.”

…while it's perfectly fine for you to say to me to ‘[reread] the quote and not just [concentrate] on the parts that catch [my] eye’, and say that my quote of Vilenkin is a bit misleading, right? 😉 Maybe it wasn't your intention, but your take of the theorem, as I've already shown, is misleading all the same.

1. Even Garrick's UGM concedes that the universe must have had an absolute beginning.. Anyway, the basic presupposition that the BGV Theorem proves that the universe had an absolute beginning isn't wrong (and I'm sure you already know that I have quotations from Vilenkin to that effect). When you want to get into subtleties, of course there are exceptions to the theorem but the problem is that none of those exceptions work (since they universally run into intractable problems) so I'm still not wrong when I say that the BGV Theorem proves that the universe must have had an absolute beginning.

Here, let me simplify it for you:

(1) If the exceptions to the GBV Theorem do not work, then the BGV Theorem proves that the universe must have had an absolute beginning. (x -> y)

(2) The exceptions don't work. (x)

(3) Therefore, the BGV Theorem proves that the universe must have had an absolute beginning. (∴y)

2. They evade the theorem because their average expansion rates aren't greater than zero.

3. That remains to be proven, of course. 🙂

But the exceptions do work and have no "intractable problems". :/ Vilenkin himself says that a prior contraction avoids the BGV singularity prediction.

Aguirre explains why Craig and Sinclair's objections are unsound,

"First, there is no singularity—that is the whole point [of the model]… In the Aguirre-Gratton type model, the idea is to generate a steady state. If you do so, you can use the BGV theorem to show that there is a boundary to it. We have specified what would have to be on that boundary to be consistent with the steady state, and argued that this can be nonsingular, and also defines a similar region on the other side of that boundary… In the natural definition of this model, there is no earliest time, and all times are (statistically) equivalent."

Again, as Carroll emphasizes, the BGV theorem is a GR theory. It does not account for the physics of quantum mechanics that would dominate at the smallest scales.

Sorry but I can't really reply as much as I want to as IntenseDebate is pushing me to my wit's end (what with these constant "your login session has expired" and "your connections has timed out" crap). I literally am rendered incapable of posting most of the time.

Anyway, the Aguirre-Gratton Model is a model that evades the theorem by stipulating that "the arrow of time reverses at the t = –infinity hypersurface, so the universe ‘expands’ in both halves of the full de Sitter space". In other words, time flows in both directions (both 'forwards' and 'backwards') from the initial singularity.

The problem? As Craig points out, the other side of the de Sitter space is not our past. The other side of the de Sitter space bears no temporal relation with anything on our side (not even the possibility of it).

Besides, as Craig surmises, the primary reason this scenario fails is that "this gross reconstruction of time denies the evolutionary continuity of our universe which is topologically prior to t and our universe".

I know the BGV to be a moot point from the moment you brought it up, but I think in these kind of discussions about 'proof' it's important that this kind of inaccuracy (from my point of view, it goes without saying) about a theorem does not go unchallenged.

XIII (emphasis mine): '[T]he basic presupposition that the BGV Theorem proves that the universe had an absolute beginning isn't wrong (and I'm sure you already know that I have quotations from Vilenkin to that effect). When you want to get into subtleties, of course there are exceptions to the theorem but the problem is that none of those exceptions work (since they universally run into intractable problems) so I'm still not wrong when I say that the BGV Theorem proves that the universe must have had an absolute beginning.'

To what effect? Well, let's consult Vilenkin.

Vilenkin: '[I]f someone asks me whether or not the theorem I proved with Borde and Guth implies that the universe had a beginning, I would say that the short answer is "yes".'

So, Yes: it implies the universe had a beginning. Does it prove the universe had an absolute beginning? Vilenkin says No. XIII says yes.

Vilenkin: '[T]he words “absolute beginning” … raise some red flags.'

Does the theorem prove that the universe must have had a beginning?

XIII: 'Yes.'

Vilenkin: 'No. But it proves that the expansion of the universe must have had a beginning.' ('Absolute beginning' raise some red flags.)

That 'but' subtlety is worth getting into—I think moreso by you—since it's actually that 'but' part that is of use to you: it is when you actually have him on record say anything about proofs about beginnings of some kind (except of course that he's talking about the expansion(s) itself).

We have three other relevant and competent physicists say the same thing as Vilenkin does about what the theorem does and does not prove. One would've thought the views of these authorities count for something … esp. having seen you pull an argument from authority when it suited you when trying to knock down one of Garrick's points.

How you can still say you are not wrong in saying the theorem proves an absolute beginning to the universe beggars belief.

This is the last I'll say anything about the BGV because it looks like it might hamper discussions bet. you and Garrick on the other important—perhaps more critical—points on the personhood arguments and counter-arguments from both sides. (Unless of course this BGV crops up again, then I have no choice but to respond to it.)

Speaking of personhood… I have, I think, what may be a counter to the changeless (and/or atemporality) feature of the person-ful God, should he be the first cause, so I'll run it by you and Garrick and forego the BGV objection for now. I'll put it up, time-permitting, as soon as it's in a coherent form.

(One last thing. You stress, 'Even Garrick's UGM concedes that the universe must have had an absolute beginning.' True. But don't forget it's you who wanted to relegate the UGM into being part of the universe in the first place, so we are where we are not for anyone but yourself. 🙂 )

Part1

Let's recap. Let's deal with each premise in turn and address your objections to each in turn.

(2) The universe began to exist.

Much of the confusion stems from the fact that we seem to be using two different definitions for the word 'universe' so let's define it here. I propose that the most plausible definition of the word 'universe', as contained within the discourses typically broached when discussing the KCA, would be as 'the set of all contingent objects (whether abstract, platonic or concrete)'.

This does not, for example, rule out your UGM. Much of my reservations (regarding your objections) are also rendered moot since we are, it seems to me, in agreement that the universe began to exist but differ as regards to what caused it.

That brings us to the first premise:

(1) Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

Self-explanatory. This is the metaphysical underpinnings that provide the foundation of the KCA and what differentiates it from other formulations of the Cosmological Argument. This is basically a non-local Causal Principle (CP)

Again, we seem to be in agreement here since your UGM postulation requires this premise to be true.

(3) Therefore, the universe has a cause.

Shouldn't be controversial since this conclusion necessarily follows from the truth of premises (1) and (2) which seems to me that we are in agreement on.

Part 2

And finally, there's:

(4) Conceptual analysis of the properties of this first cause yields characteristics that are of theological significance.

This one is where our chief disagreement lies. You maintain that (4) is plausibly false by virtue of the fact that this hypothetical first cause need not be a personal mind. This implies that nothing of theological signifiance actually follows from the initial conclusion (3) of the KCA.

An ultramundane cause of the universe that is not a person but is enormously powerful, timeless, spaceless, immaterial, beginningless, changeless, uncaused need not actually have any notable theological implications since a UGM seems a perfectly plausible alternative.

I've three problems with this conclusion:

1. It does not follow from the fact that the FC need not be a person that the FC is, in fact, non-personal. It's a non-sequitur. There's a large difference between a KCA that fails completely in proving theism to a KCA that points to an FC that might be God.

2. You point out that conceding that probabilistic causes are possible is sufficient to explain how a temporal effect could have come from a timeless cause. This is false (though I missed it before) since the FC is changeless (at the very least, prior to the universe's origination).

The FC is changeless because an infinite regress of events is impossible (and change is an event). This prima facie rules out probabilistic causation as regards to the FC.

3. Moreover, change implies temporality as the UGM transitions from one probabilistic event to the other (that either actualizes or fails to actualize). A further postulate necessary for your probabilistic UGM is, in fact, the existence of time (directly contradicting some of your earlier statements). In fact, a succesion of events is pretty much definitive of what time is (especially on the relational view).

The arguments for the personhood of the FC stills stands. Cheers. 🙂

I will just clarify that time is not simply changes in a system (since a tunneling particle changes in position but experiences no time at all while within an energy barrier). It is a specific parameter in physics that takes entropy (number of states) in a system. The UGM has no time and no direction in time since it never has net change in entropy (all universes are zero total energy). I'm afraid that our different conceptions of time is guilty of much of our misunderstanding. So, strictly speaking, while the UGM has universes bubbling in and out of it, the UGM itself remains timeless since it has no space parameters or entropy to speak of.

I think we can agree that the universe, that is, our specific universe, began to exist and has a cause. In other words,our space-time continuum has an ontological prior.But, if the definition of universe is everything that is physical or logically contingent, (including the UGM) then I don't think the Kalam is successful.

As I stated elsewhere the Kalam's Causal Principle appears to use one example to create an all-encompassing metaphysical rule. I will reformulate it here based on the clarifications you and I have put forward.

Everything that we know to exist has our specific universe as its causal condition—the matter particles that make up you, I, and the computers we are using to communicate. That is, their beginning of existence is synonymous to the beginning of the existence of our own universe.

So, in the Kalam's metaphysical intuition that is the causal principle, it seems to only refer to one example to prove that the natural causal conditions of our universe (UGM) began to exist. If you'll allow me, this seems to me what the Kalam looks like once the broader natural picture is taken into account. I also clarify the different meanings of "begin to exist" such that the equivocation of the Kalam is clear.

(1) Everything that begins to exist in our universe has our universe as its cause.

(2) The universe itself began to exist.

(3) The natural causal conditions of our universe have a cause.

I think you'll agree with me that this is a nonsensical conclusion. I also think that this is the only scientifically informed version that the Kalam can take.

(Part 3 of 3)

On another front, Leibniz’s form of the cosmological argument was put forward. Classical cosmological arguments were made under the view that the universe is eternal. I clarify my position that the UGM is logically contingent but causally independent. I also argue that while Leibniz’s principle of sufficient reason may survive attacks from quantum indeterminacy, using it to prove the existence of a necessary being is question-begging. This is because the principle cannot be true if necessary beings don’t exist because this would result in an infinite regress of contingent beings explaining each other’s existence (which is a priori impossible, rendering the principle false). A weak form of the principle of sufficient reason states that beings that exist must have explanations, either in other beings or by necessity of their nature. The principle can only be true if we already assume that at least one necessary being exists. Therefore, its application in proving the existence of a necessary being is circular.

(Part 2 of 3)

_XIII_ questions my use of quantum mechanics to refute the personhood argument for the identity of the first cause. I argue against the personhood argument’s assumption that mechanistic causes must have their effects take hold immediately. If this is the case then the universe must exist through an infinite series of events in time (which is impossible!) since the cause of the universe is eternal. Quantum mechanics shows a naturalistic process where conditions can be present without the effect occurring immediately. I don’t think this point was adequately challenged so I consider, at the very least, the particularizer argument for the personhood of the first cause defeated.

However, two other arguments about the personhood of the first cause were presented. Namely, (1) there are two types of explanations: scientific/naturalistic and personal. Since the singularity phase of the universe cannot have a scientific explanation since it was outside space and time, then the first cause must be personal; (2) there are only two kinds of immaterial, uncaused, timeless, and spaceless things: abstract objects (propositions, numbers, etc.) and personal minds. And only personal minds could be causally effective (propositions cannot cause anything to occur).

I argue that a possible naturalistic mechanism exists as elucidated by a quantum theory of gravity. I admit that such a theory is far from established and needs a significant amount of work. But, as I explain, we can reasonably speculate on what such a theory will contain when general relativity and quantum mechanics are reconciled. As has been shown by scientists such as Lawrence Krauss, expanding the sum-over-histories approach by Feynman to space itself will result in quantum gravity explaining how space can itself appear spontaneously. These spaces will be tiny self-contained highly compact universes with a zero total energy. This would therefore not violate laws of conservation since gravity counts as negative energy versus the positive energy of matter. This idea is not logically impossible, therefore it is not necessary for the explanation for the universe to be personal. Our own universe appears to have a zero total energy.

Furthermore, this era that is ontologically (but not temporally) prior to our universe, which I will call the universe-generating mechanism (UGM) is exactly this: timeless and spaceless. It is, however, not devoid of potential, so it will not satisfy the theologian’s desire for absolute nothingness (which seems to require the special pleading of a lack of all potential except supernatural potential). In fact, quantum mechanics shows that absolute nothingness is unnatural. The uncertainty principle simply requires that out of the absence of space and time, space must spontaneously appear. This is a rather counter-intuitive state of affairs that I don’t think could ever have been the result of armchair philosophy. Therefore, I can justifiably refute the two objections: that our universe cannot have a scientific explanation and that only personal minds are the only causally effective timeless and spaceless things.

However, what about the explanation of this UGM? Would its existence and nature admit of a scientific explanation? Here I would readily concede, no. I believe this is simply a brute fact. I do not even believe that this UGM is logically necessary since its non-existence does not result in contradictions. Its existence is inexplicable. I also do not think that a personal God is necessary to explain the UGM’s existence since it is already eternal and timeless and it certainly is not clear that it can even have a beginning of existence.

I’ll try to summarize here as fairly as I can the very lively and interesting discussion that has gone on so far. I will change phrasing that I used as I found a lack of clarity in my own views, which were gradually refined by the challenges presented. My thanks to Pecier, Miguel, innerminds, and _XIII_.

(Part 1 of 3)

My article here shows that William Lane Craig problematically switches between different views of time: absolute and relational. The former assumes that time is metaphysical. As I said, I personally have trouble understanding this definition as this is not the scientific view. The latter is the scientific view as shown through special relativity: absolute simultaneity is nonsensical and two events can counter-intuitively occur temporally prior to each other due to their frames of reference. The physicist’s time is dependent on motion and mass. I also show that the personhood of the first cause is problematic given quantum mechanics.

To argue against the eternity of the universe, Craig assumes that time is absolute. Because of this, the universe cannot have existed forever because an actual infinite series of events is impossible. At the same time, Craig argues that God is timeless in the relational view. Unfortunately for Craig, as I show in my piece, our universe also had a timeless phase, so it also has always existed (there has never been a time with no universe).

Miguel and _XIII_ in the comments section have not addressed this and I don’t think there really is anything that can be said against my argument. Craig clearly and unfairly argues against the eternity of the universe by switching his views of time depending on convenience.

my point is simple. proving the origin of the universe would not satisfy any religious dogma as they are all very local. from standpoint alone, all of them are wrong by assuming that their deity created everything and yet never mentioned about the extreme size of the universe, focused on just one planet (aside from mormon theology). this limitation points that man, in that age of intellectual gap, had filled in his limitations with his own limited reasoning.

deism is out of the point either, because that assumption was based from the thinking that a deity/creator is plausible. to think it was suggested during the time when people "live" along monsters and magical creatures.

nobody knows at this point in time. i could say the universe created itself, and it is not a god as how we define god. slipping in every deity's name in such a topic only makes things more complicated, and thus religion hasn't had simplified any answer to a question. only worsened it.

Oh where to begin..

I don't get what you mean here by what you say Craig says, but Craig says –at least in his debate with Enqvist– that most physicists don't hold to Quantum Logic, and therefore the rules of logical inference, presumably from which he derives the premises of the KCA, still hold. In fact there are many interpretations of QM that are very much unlike the one held by Hawking (Copenhagen?) in that they are deterministic. As far as I've been able to gather, there is no consensus on which is the right interpretation, but the Copenhagen one seems to be the most well-known to lay people. Nevertheless –and this challenges your use of QM to counter causality as it is conventionally understood– QM is merely descriptive; it's fallacious to infer that, because QM describes a state without describing its cause, that state must therefore not have a cause. It would be the same as saying the motion of planets have no cause because Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion speak nothing of them. In any case, so-called uncaused QM events are still based on Quantum laws and the prior conditions out from which they arise making one wonder why we are asked to throw the metaphysics of causality out the window just because we've yet to understand the principles on QM under which it operates?

Another observable folly here is that science is telling us what doesn't exist by what it cannot observe (no observable cause, therefore no cause exists). This is odd, one would think, since science in principle can only tell us what exists, or what it infers exists, from that which it can observe. You would think that science, in principle, cannot tell us what doesn't exist based on what it cannot observe, but it is doing exactly that. Of course, this isn't an argument against causality in QM –for all we know they're right; things happen in QM for which there is no cause– but rather that, if that were indeed the case, science cannot in principle tell us about it.

So much more I can say about your post, but the above will do for now.

There are actually very few deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretation_of_qu… Even then, deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics can still hold that many states exist at the same time (such as the many-worlds interpretation). Hidden variable interpretations such as the deBroglie-Bohm interpretation have largely fallen out of favor.

In any case, I don't have to hold that quantum mechanical events are "uncaused." I said this in my piece, which should answer all of the objections listed here.

You concede, I think, more than you intend, since, if you won't go the universe-is-uncaused route ("I don't have to hold QM events are uncaused"), that leaves you with one option: the universe caused itself (or if you believed in a multiverse, then the multiverse caused itself).

The problem with this is that people who say this –like Hawking– don't seem to know what it entails. It would entail that the universe itself is a necessary entity; the universe exists out of a necessity of its own nature. One thing we know about the universe is that it's contingent –and therefore cannot exist out of a necessity of its own nature.

Another thing is that –and I hope this will be easy to follow– if the universe can cause itself, then anything can cause itself, because before the universe caused itself, there wasn't anything about the universe that would make it tend to cause itself, for before it was caused, it wasn't anything.

or

If something can come out of nothing –since that would mean it would essentially cause itself to exist out of zero pre-existing material– then anything can come out of nothing.

That's why it is argued –I think by Craig as well– that whatever caused the universe was an agent who had *intended* the universe to be as it is, and who is in principle uncaused. We have prima facie evidence, at least, that the universe cannot bring these qualities to bear.

How do we "know" that the universe is contingent? Is that not exactly the conclusion that the Kalam is trying to prove? Interestingly, quantum mechanics shows that everything (in the quantum scales) that can happen will happen. Why should the universe not be necessary?

More importantly, I contend, it is nonsensical to say that the universe was nothing before it was caused, because there was no before it was caused. There was no time outside the universe.

I think the biggest error here is assuming that the universe is comparable to any old thing. I think you'll agree that God is not comparable to ordinary things, why should the universe that began with time be comparable to objects beginning to exist in time?

The Kalam is trying to prove theism while the universe being contingent is taken as a premise. We have prima facie evidence that the universe is contingent –everything in it is. Its contingency is an expansive property and thus does not commit the compositional fallacy. This of course doesn't prove the universe is contingent, but it's still evidence that tips the scales in favor of, if not theism, then non-materialism.

It doesn't matter if there was "no time outside the universe", something need not be chronologically prior to be ontologically prior. In fact, you echo this in your post when you imply quantum energy is that eternal thing from which the universe emerges. Krauss and Hawking may bandy about the 'north of north pole' argument whenever it suits them, but they still make implications of other universes and universe-generating mechanisms from which our universe has its ontology.

Even if I grant you that quantum energy –or whatever it's called–, from which the universe emerges, is non-contingent, and therefore, necessary, you will still fall in the same rut of which I previously mentioned; this quantum energy will necessarily have causal qualities to it that would make it tend to create universes and not, say, pink bunnies. Thus, we can still ask why it creates what it creates and not pink bunnies? And there could be 3 possible answers about the nature of this eternally existing and necessary thingy:

1. This Q energy is just that way. (which is unsatisfactory)

2. This Q energy has intention. (Deepak Chopra will be pleased)

3. Actually, it can create pink bunnies. (patently absurd)

Neither of which you, Hawking, Krauss, or anyone else has philosophical or scientific arguments to back up, and therefore seems to amount to nothing more than a post hoc rationalization that's neither based in science or philosophy, but flouted anyway in support of strongly held anti-theistic metaphysical commitments.

I think I wasn't clear by "contingency" so, for that, I apologize. Yes, the universe is logically contingent, in that not every world will have a universe exactly like ours and its non-existence would not result in contradictions. If a set includes contingent stuff, then it must be contingent itself since the set could be composed of other stuff (as in pink bunnies). However, how do we know that the universe is ontologically contingent? Is this not what the Kalam is trying to prove?

It's completely possible that the universe is simply ontologically necessary, or non-contingent (to be clearer 🙂 ). Its existence is not dependent on some other thing since it is eternal. Being such, it would be a brute fact. The universe's eternity is supported by general relativity and escapes the impossibility of an actual infinite.

Since the eternal universe is logically contingent, but ontologically non-contingent, any explanation for its existence would be nonsensical, even with an appeal to a logical necessity such as a god. (For that matter, how do we even know that actual logical necessities can even exist?)

If the universe is logically contingent and ontologically non-contingent (eternally existing) then no explanation, not even a logical necessity, can be its "ontological prior." That would mean that if the universe is necessarily entailed by the logical necessity it would be itself a logical necessity, which would contradict its logical contingency. It would also mean, whether it was logically necessary or logically contingent, that it is no longer ontologically non-contingent, if it has a cause, God.

The Kalam tries to show that the universe is ontologically contingent. Therefore, to assume that the universe is ontologically contingent is to beg the question.

I think that if you do, as you did, grant the logical necessity of the laws of nature then our debate would be composed of cosmology and no longer abstract philosophy. We would then discuss symmetry breaking and fundamental forces that would lead to our current state of affairs. That would be the context in which we can ask why it creates what it creates.

Even if it the universe were eternal, that does not entail it would need no explanation, in fact the previous versions of the cosmological argument assumed the universe was eternal. But, hell, my head is spinning from all these words. Let's just leave it at that, and once again thanks for this exchange.

As I lay out in my previous response, ontologically non-contingent beings, such as the universe, cannot be explained, in principle. To try to would result in logical contradictions.

Thanks as well, Miguel! 🙂

And I was just about to bring out the popcorn. You two shouldn't get too friendly with each other cause it takes the fun out of watching you debate. 🙂

[Even if it the universe were eternal, that does not entail it would need no explanation]

Does this mean that God's presumed eternal existence requires an explanation as well?

[the previous versions of the cosmological argument assumed the universe was eternal]

Correct me if I'm wrong, but from what I can remember, previous versions simply stated that everything that exists has a cause, and that's why they had to refine it into "everything that begins to exist" or else they would be committing special pleading by saying that everything that exists has a cause except God.

"Does this mean that God's presumed eternal existence requires an explanation as well?"

Well, to take the Leibnizian version: whatever exists that derives it's reason for existence outside itself must ultimately, down the line, derive existence from that which has its reason for existence in itself.

In other words, whatever is contingent must ultimately derive its existence, down the line, from something that is not only non-contingent, but necessary –something that couldn't, in principle, have failed to exist, and something that, in principle, cannot be said to have had a cause or an explanation. The whole point is to show that there HAS to be something like this –so nothing is posited arbitrarily. Therefore it makes no sense to ask, as Dawkins does, what the cause of God is.

My contention was that there is nothing in this universe that seems to exist necessarily. If scientists think there was –like Quantum energy– I'd be glad to hear the arguments in support of it. Of course, that's not all I can say about that, but leaving that aside for the moment.

"Correct me if I'm wrong, but from what I can remember, previous versions simply stated that everything that exists has a cause, and that's why they had to refine it into "everything that begins to exist" or else they would be committing special pleading by saying that everything that exists has a cause except God."

Let's just say there are many versions. Aquinas assumed the universe was eternal, and the others –like Leibniz I think– did not formulate their arguments in consideration of the universe's beginning. The point is that even if every state of the universe was caused by a previous state that extended infinitely to the past, that does not entail that this collection of states exist necessarily. We can still ask why this collection of states exist, and since the collection of states do exist, then the question is still a meaningful one. In other words, previous versions sought to answer just that 'why' question without consideration of any beginning point.

[My contention was that there is nothing in this universe that seems to exist necessarily.]

I would like to point out, as Garrick did, that the universe did not begin to exist in time. Time itself is contingent upon the universe’s existence. It’s not like there was a time when there was no universe. And with this I contend that unless there is an absolute time or a “time beyond time,” the universe is a necessary entity because time exists.

Innerminds,

like I said to Garrick, however, one need not be chronologically prior to be ontologically prior. So this argument of yours which is identical to the 'north of north' pole one doesn't really obviate the question of what caused the universe or whether it's necessary.

May I ask what are the arguments to support the contention that God is ontologically prior in addition to being chronologically prior that cannot be applied to the universe or to whatever universe-generating mechanism?

Well with respect to the cosmological argument –and all its variations– they can be applied to the universe and whatever universe generating mechanism; I mean, you can reformulate the Kalam to try and show the universe or the UGM is the thing that in principle has to exist from which everything else owes its existence. But the conclusion, for me at least, becomes fantastically more improbable for reasons I've given above.

It's like the CA argues that down the line, that's what in principle must exist (and then Aquinas spends hundreds of pages exfoliating this conclusion and inferring the characteristics of God), while science, on the other hand, is saying that since it can only account for X, therefore X is what ultimately is down the line, therefore X is that thing which in principle has to exist, and even if it can be accounted for, it will just say it's inexplicable (since it will really be, in principle, inexplicable).

Now, if you're telling me that's a warranted conclusion on the part of science, then fine. We'll be at an impasse. But,really, it will be laughable if a scientist says it's a "scientific" conclusion, because it clearly isn't.

[science, on the other hand, is saying that since it can only account for X, therefore X is what ultimately is down the line, therefore X is that thing which in principle has to exist]

That doesn't sound like science. Science would more likely say something like, "After reviewing the available evidence as of this time, we can only account for X and there is no evidence to support the existence of something prior to X."

[and even if it can be accounted for, it will just say it's inexplicable (since it will really be, in principle, inexplicable). ]

Doesn't this sound very much like what the theists would say about God as the necessary cause, that his existence, consciousness, and power (including his ability to exist beyond time) are all inexplicable?

[Now, if you're telling me that's a warranted conclusion on the part of science, then fine. We'll be at an impasse. But,really, it will be laughable if a scientist says it's a "scientific" conclusion, because it clearly isn't.]

Of course it's in no way a warranted conclusion on the part of science. But that goes the same for the conclusion that the universe was caused by God.

By the way, Miguel, could you please add me up on Facebook? You know my full name so you can search me. 🙂

"That doesn't sound like science. Science would more likely say something like, "After reviewing the available evidence as of this time, we can only account…"

Tell that to the gnu atheists then, because, that's not what they do, actually.

"Doesn't this sound very much like what the theists would say about God as the necessary cause, that his existence, consciousness, and power…"

Aquinas spends hundreds of pages inferring these characteristics from the argument's conclusion –so does Craig. I think you should read their papers and see they're doing nothing of the sort. Obviously, many characteristics about God will be inexplicable, but remember, the CA only gets you to soft theism. The other things Christians know about God they learned from revelation.

"Of course it's in no way a warranted conclusion on the part of science. But that goes the same for the conclusion that the universe was caused by God. "

I'm sorry but no. Again, read at least Craig's whole explication of the Kalam. He doesn't posit anything arbitrarily. Or read Aquinas's 5 ways (you will however have to first understand his metaphysics, or you'll completely miss his points.)