Year of the Solar System

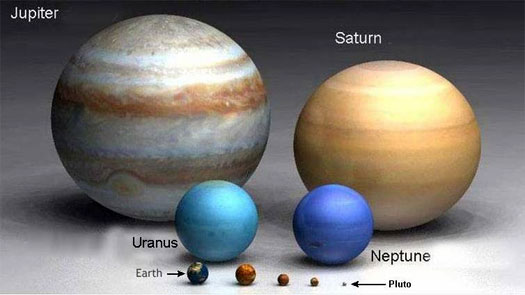

Happy Year of the Solar System! The planets are so happy to greet you they decided to move too close to each other just so that they could fit in a family portrait to show you. Also, so as not to dwarf their smaller siblings, the giants of the family had to move a lot farther from the camera.

Shown below is a more candid family portrait. Here, the planets are shown in their correct size relationships.

But how far are the planets with respect to each other? When I taught high school astronomy two years ago, I tried to draw a Solar System that’s to scale on our classroom’s white board. Good luck to me! I ended up either trying hard to include Jupiter in my drawing or attempting to carefully draw the crammed orbits of the inner planets just so that they’re distinguishable from each other. In the end, I used a number of steps to illustrate the relative distances of the planets to each other. (“If the Sun were here, then Mercury would be so and so paces away.”)

Before we go to the relative distances involved in our cosmic neighborhood, let us first have a word about the units we use to measure the Solar System.

Measuring the Solar System

The average distance of the Earth from the Sun is about 150 million kilometers. If you could fly to the Sun in a spacecraft that travels at three times the speed of sound, it would still take you more than 5 years to get there! So that we don’t have to be inconvenienced by humongous numbers in describing distances within the Solar System, astronomers invented the astronomical unit (AU). 1 astronomical unit is equal to 150 million kilometers, the average distance of the Earth from the Sun.

How Many Steps from the Sun?

Using the astronomical units, the distances of the planets from the Sun can be written in convenient, sizable numbers. These numbers are shown in the table below.

| Planet | Average orbital radius (AU) |

| Mercury |

0.4 |

| Venus |

0.7 |

| Earth |

1 |

| Mars |

1.5 |

| Jupiter |

5.2 |

| Saturn |

9.6 |

| Uranus |

19.2 |

| Neptune |

30.1 |

The second column is labeled average orbital radius because a planet’s average distance from the Sun is indeed the (average) radius of its orbit.

Now, let us make our mini Solar System. Imagine the Sun to be where you are right now. (Better yet, imagine you are the Sun.) If you take 4 steps from your current position, you’d get to where Mercury is. To get to Venus, you have to take 7 steps from where you are, while you need to take 10 steps to get to the Earth. Meanwhile, you need to take a good 15 steps to get to Mars’ obit. So far, so good.

But wait, notice that to get to Jupiter, you need to take no less than 52 steps! Jupiter, it turns out, is more than three times as far from the Sun (that’s you) as Mars is. Why is there so much empty space in between Mars and Jupiter?

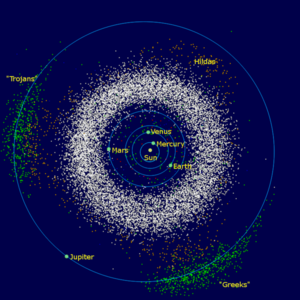

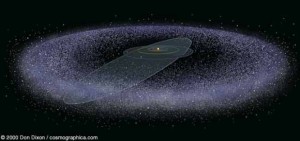

Well, as most of us know, the space between Mars and Jupiter is far from empty. Rather, the space is populated by a swarm of rocks called the asteroid belt. Some of the asteroids are so large they are considered dwarf planets. Many scientists think that they are rock fragments that failed to coalesce into a planet during the Solar System’s formation because of the constant gravitational tug of neighboring Jupiter.

But don’t imagine the asteroid belt to be a densely clustered group of flying rocks. Although the asteroids number by the hundreds of thousands, there’s plenty of space for them to distribute themselves in.

Now let’s go back to our walk through of the Solar System. We learned that if the Earth is 10 paces from the Sun, then Jupiter is 52. Meanwhile, Saturn would be 96 paces from the Sun. Saturn is nearly ten times as far from the Sun as the Earth is! About twice as far out, at 192 paces, is Uranus. (No, I will not make a Uranus joke). Neptune, the farthest planet (yes, get over it), is 301 steps from the Sun.

As I am writing this, I am in a room whose biggest dimension is around a hundred steps (that’s “how far” Saturn is from the Sun). When I place textbook on one corner of this room (the “Sun corner”), I can hardly see it from the opposite corner (the “Saturn corner”). However, from the Sun corner, the positions of Mercury (4 steps), Venus (7 steps), Earth (10 steps) and Mars (15 steps) are literally within spitting distance. I highly doubt it if I can spit as far as the orbit of Jupiter (52 steps).

The Ends of the Solar System

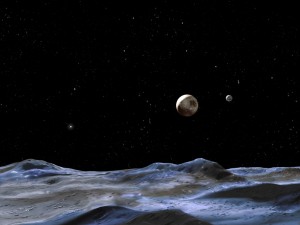

Don’t worry, I did not forget about Pluto. Just because astronomers do not consider it a major planet anymore doesn’t mean I stopped loving it.

Before we “walk to” Pluto, let me first get this out: nothing “happened” to Pluto. No, it did not become a moon of Neptune. It did not even shrink. Above all, it did not become a star!

If you’re wondering why I had to say this, good for you. Many people – and I mean many – believe that something happened to Pluto to deserve its “demotion” from being a major planet to being a dwarf planet. And yes, some people think it became a star. (Well, in a sense, it became a ‘star’. But you know what I mean.)

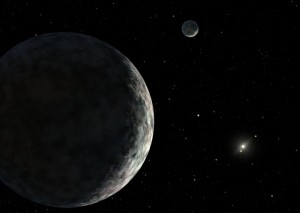

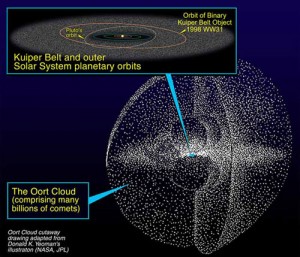

I think the misunderstanding surrounding Pluto’s planethood (or stardom) reveals the natural human tendency to be essentialists. In other words, most people still think that to be a planet, one must have the essence of a planet – one must possess planetness. That truth, however, is that ‘planet’ is just another word for ‘biggish object orbiting a star’. In this case, the star is our Sun. And we get to decide how big is big. The problem with Pluto is not just that it’s really small, it’s that we found at least one other object orbiting the Sun that’s bigger than Pluto. That object is Eris, named after the goddess of discord and strife. Along with Pluto, Eris is part of the Kuiper Belt, a second belt of rocks orbiting the Sun. Most of the Kuiper Belt lies beyond the orbit of Neptune. Other members of the Kuiper Belt have names like Sedna, Xena (the warrior princess), Makemake and Haumea.

Now, let’s go back to our walk through. Recall that in our mini Solar System, you are the Sun. 10 steps away is the Earth, 52 steps is Jupiter and 301 steps is Neptune. Pluto is, on average, 395 steps from you. The Kuiper Belt starts at around 300 paces. To get to where Eris is, you have to walk 1,000 steps from where you are. If you think the Solar System ends there, then you couldn’t be more wrong. The Oort Cloud, a hypothetical body of rocks and comets, is no less than two thousand times farther from the Sun as the Earth is. That means that if the Earth is 10 steps from you, then the Oort Cloud is 20,000 steps away! Some astronomers even think that the heliopause, which could be thought of as the outer boundary of the Solar System, is no less than 500,000 steps away. The inner planets are indeed in the innermost part of the Solar System.

Sola!

That concludes our overview of the vast dimensions in our own cosmic neighborhood. I hope the “walk through” inspired you to make a mini Solar System in your own backyard. And I hope that the next time you look up to the heavens, you will see the grandeur that held thrall all the great minds throughout the ages.

Photo credits:

- www.nasa.gov

- www.solarsystem.nasa.gov

- www.universetoday.com

- www.wikipedia.org

- www.cosmographica.com

- www.theiamfamilyoflight.com

Wow!

I wish you could write something about Stephen Hawking's extremely controversial documentary on the Discovery Channel, Did God Create the Universe? or Does God Exist?

Hawking is my hero…

This article is a great accompaniment to History Channel's Season 6 The Universe – How Big, How Far, How Fast episode. Talks about the same thing. Watching it right now, reminded me of this piece at once. Your ability to strip down larger than life concepts to concrete terms people of all ages could relate to is remarkable. Great work, thanks!