In the coming days, stargazer the world over are swooning like fanboys and fangirls over the arrival and surprising intensification of Comet ISON. In this article, we will give some of the reasons why astronomers all around the world are geeking out over the comet. We will also give some tips that will be helpful in hunting for this celebrity comet.

Comet ISON is virgin stuff

Comet ISON was discovered by amateur astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novitchonok using telescopes run by the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON). According to calculations of its orbit, Comet ISON is a “dynamically new” comet. This means that this visit to the inner Solar System is Comet ISON’s first, and probably also its last.

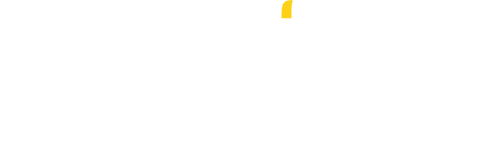

This makes planetary astronomers jizz in their pants because closely studying a first time visitor to the inner Solar System is a chance to peer into the origin of the Solar System itself. Some comets, for example the famous Halley’s Comet, are periodic comets. This means they periodically shuttle between the Kuiper Belt, that region beyond Neptune’s orbit to which Pluto belongs, and the inner Solar System. Thus, periodic comets are used to getting baked by the Sun’s heat and radiation. Dynamically new comets like Comet ISON, on the other hand, are former denizens of the part of the Solar System called the Oort Cloud. The icy bodies that form the Oort Cloud are believed to be remnants from the formation of the Solar System some 4.6 billion years ago. As Comet ISON approaches the Sun, the stuff it is made of will be exposed to the Sun’s heat and radiation for the very first time ever since the Solar System’s formation, so the gas and dust it will release can tell us about what kinds of stuff there were around during the time of the planets’ formation.

Comet ISON will live life dangerously by grazing the Sun

Comets have very eccentric, that is elongated, elliptical orbits. This explains why they are sometimes very far from the Sun and also sometimes very near it. A class of comets called sungrazers put the mythical Icarus to shame by getting so close to the Sun that the star’s tremendous gravitational field starts to tear at them. Many of these sungrazing comets do not survive their close approach to the Sun in one piece. Of the sungrazers that bite the dust, some evaporate completely while others dive into the Sun. Others still break into several large pieces that, taken as a team, put on a spectacular show. One good example is the Comet Ikeya-Seki, a sungrazing comet that broke into three to five large pieces as it approached the Sun. Comet Ikeya-Seki is considered one of the brightest comets of the previous century, reaching a brightness that made it visible in the sky even during noon. Like Comet Ikeya-Seki (which graced the sky on 1965) and the dazzling Comet Lovejoy (which put on a show last 2011), Comet ISON is also a sungrazer.

![A sungrazer comet. [Photo credit: wikimedia.org]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/sungrazer.png)

An orbiting body’s closest approach to the Sun is called its perihelion. Comet ISON will reach perihelion this 28th of November. During this time, it will be three times closer to the Sun than Mercury ever gets.

Sungrazer comets always put space geeks on the edge of their seats because it is so hard to predict whether a sungrazer will survive its perihelion. Many astronomers think that Comet ISON’s prospects for survival are high, but until the 28th of November the jury is still out.

Aside from glancing off the Sun, Comet ISON has one additional claim to fame of being unique among sungrazers. Most sungrazers belong to a family called the Kreutz Sungrazers, a family of dangerously living comets that have related orbits and are believed to be fragments of the same parent comet. Both Comet Ikeya-Seki and Comet Lovejoy, as well as many other famous sungrazers, belong to the Kreutz family. Comet ISON is not part of this gang.

Comet ISON’s story is always a cliffhanger

The closer a comet gets to the Sun the brighter it shines, reflecting the most light from the Sun when it’s near perihelion; like nearly everything in the Solar System, comets do not produce much of their light, but instead merely reflect the Sun’s. It is therefore not surprising that sungrazers have the potential to be really bright, a fact illustrated by Comet Ikeya-Seki and Comet Lovejoy.

This lead some writers to prematurely hail Comet ISON as “the comet of the century”. Early this year, it became clear that this is certainly an exaggeration. This lead some astronomers to swing to the opposite side of the optimism spectrum by predicting that Comet ISON will be a dud.

Astronomers are not new to comets that do not perform as was initially hoped. The most famous example was the Comet Kohoutek of 1973. Kohoutek was considered an astronomical PR disaster because of the hype that grew around it and the subsequent lackluster performance. Some astronomers fear that Comet ISON might be a Kohoutek Part II.

![Comet Kohoutek did not live up to the hype. [Photo credit: Photo credit: light-headed.com]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Kohoutek.png)

Well guest what, in recent nights Comet ISON surprised everyone by suddenly brightening! It still is not as bright as previous optimistic estimates predicted, but recent developments also give the lie to the pessimists’ projections. In other words, Comet ISON is frustrating most attempts to divine its maximum brightness.

What was just said is not an indication that astronomers are clueless but rather an illustration of the amazing variety of comets; there are just so many kinds of comets that it’s very difficult to predict the behavior of the next comet based on the behavior of its predecessors. This lead the great comet hunter David H. Levy, of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 fame, to famously say, “Comets are like cats; they have tails, and they do precisely what they want.”

That’s all fine and good, but where in the freakin’ sky do I find this cat?

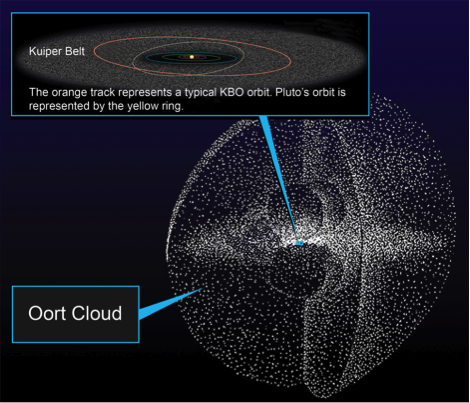

Right now there are three requirements if you want to see Comet ISON. First, you must wake up really early, around 5 in the morning. Second, you must look for the constellations Virgo and Libra. If you don’t know how to find these faint constellations, fear not. If you look toward the easter horizon at the early hours of the morning, you will be inevitably looking at these two constellations. The third requirement is a modest pair of binoculars. As of this writing, Comet ISON is already barely visible to the naked eyes on a dark sky. Using a pair of binoculars allows you to see Comet ISON as a faint smudge with a distinct tail.

The screenshot shown below is from the freeware Stellarium, a free software that you can download from this link. In the screenshot Comet ISON is indicated by its official name, C/2012 S1 (ISON). The position shown would be the spot where Comet ISON can be found at around 5:15 AM on November 23 in Manila.

As the date of perihelion approaches, Comet ISON will move farther from the location of Mars in the constellation Leo and towards the center of Virgo, to the direction of the Sun.

Do I need to buy expensive telescopes just to see this thing soon?

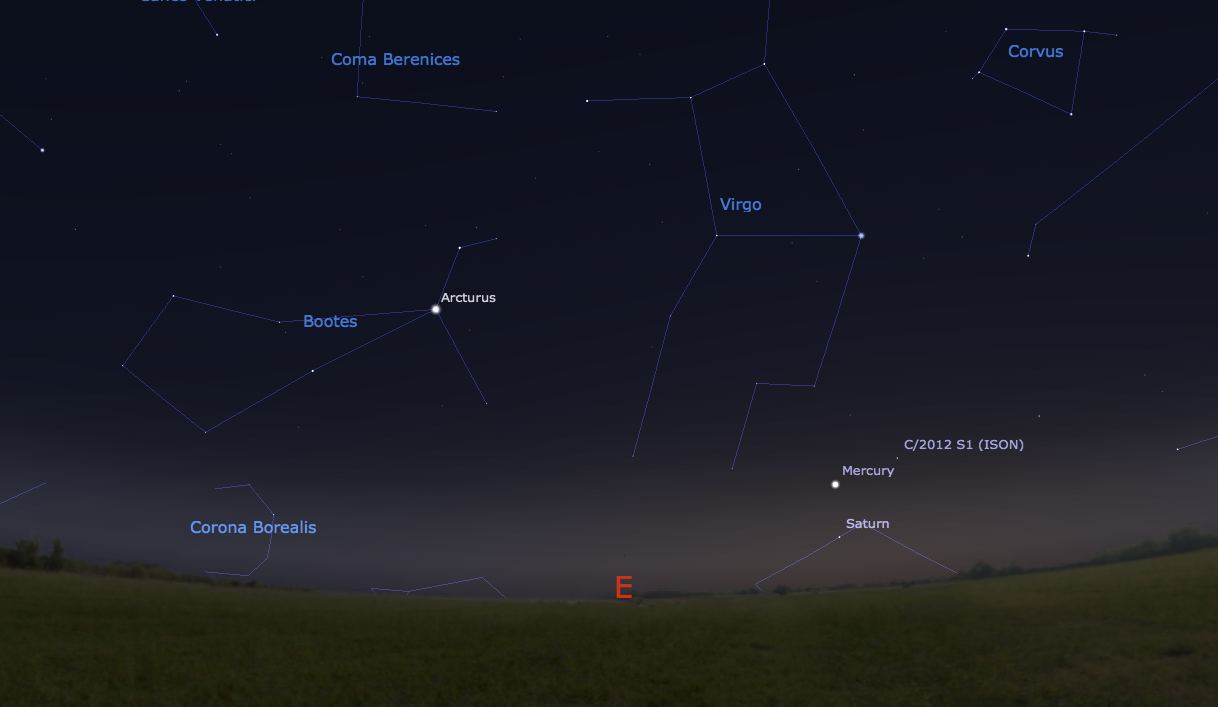

Fortunately, you don’t have to. As of this writing, Comet ISON is bright enough to been seen through a modest pair of binoculars, and its getting brighter and brighter by the hour. Many stargazers have even noted that the comet is visible via the naked eye in dark locations, and it might intensify further to be visible even in urban vantage points! If this prediction proves accurate, Comet ISON will probably put on a good show after its perihelion next week and further into December.

At any rate, Comet ISON’s claims to fame are enough to make it a comet worthy of intense observation. Whether it will be among the brighter comets of recent years or a modest naked-eye comet, Comet ISON will be among the most closely observed comets in history, and everyone is invited to join in this celebration of human curiosity.

![A November 17 photo of Comet ISON taken by Austrian astrophotographer Michael Jäger. Note that the comet's beautiful and long tail is still too faint to be seen with any detail via naked-eye observation. [Photo credit: Michael Jäger]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/2D9728011-131118-coslog-comet2-345p.blocks_desktop_medium-1.jpg)