Now and again I am gripped by this nagging suspicion that maybe Carl Sagan was overrated as a science communicator, and that perhaps my memories of him are false memories generated by a halo effect. Such suspicions are often attended by this feeling that his message would, by now, be awkwardly dated if not silly and shortsighted in the context of the twenty-first century. Or maybe, like many thinkers I once held in high regard, I have already grown out of my admiration for him.

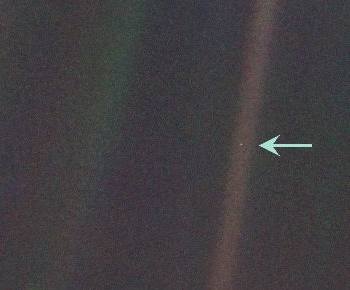

During such times, I check the evidence that is Sagan’s considerable body of work in science popularization. After all, Sagan himself always stressed the value of evidence. Part of my methodology involves going to YouTube. There I look up Carl Sagan’s reflections on the Pale Blue Dot. I play the video. “From this distant vantage point, the Earth may not seem of any particular interest,” begins Sagan’s sonorous voice, referring to the vast distance from which the photo of the Earth was taken. “But for us, it’s different. Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us,” he continues, his cadence impeccable, his perspective both mesmerizing and undeniable, his passion nothing short of contagious. By the time the video ends, my eyes are sopping with tears. This happens every single time.

It was on Carl Sagan’s request that the Voyager 1 space probe took the famous Pale Blue Dot image from across the vastness of interplanetary space. Being both an astronomer and a science communicator, he knew right away that it was an opportunity for him to share with others, in the form of an actual photograph, his sense of cosmic perspective.

Even to this day, his reflections on the photograph have not lost one iota of their force. If anything, they are more significant today than ever. Observe, for instance, the relevance of the following lines to the currents state of world affairs: “Think of all the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner.” Note how carefully chosen the words are. They aren’t just about humans, they are about the inhabitants of the pixel. All of them. To give another example, consider how the following lines gain added significance in the light of our current understanding of climate change: “The Earth is the only world known, so far, to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment, the Earth is where we make our stand.”

![The photograph known as the "Wave to Saturn" or "Pale Blue Dot 2.1". It was taken by the Cassini space probe in 2013. "Pale Blue Dot 2.0" was also taken by Cassini in 2006. [Photo credit: NASA]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/pale-blue-dot.2.1.jpg)

It was this keen understanding of the problems we face as a global civilization and the role science plays in solving them that made Carl Sagan’s approach to science popularization unique, poignant, and relevant. The link between promoting science and empowering people was central to why he wanted people to understand. In an interview with Charlie Rose months before his death, he said, “We live in an age based on science and technology with formidable technological powers… And if we don’t understand it — and by ‘we’ I mean we the general public — if it’s something that [makes us say], ‘Oh I’m not good at that, I don’t know anything about it,’ then who is making all the decisions about science and technology that are going to determine what kind of future our children live in?”

Carl Sagan understood that democracy and science were intimately intertwined, that true democracy was not possible if the citizens are ignorant, and that science required an environment of independent inquiry that is difficult to maintain outside a free society. Relating his ideas to that of Thomas Jefferson, he said, “It wasn’t enough… to enshrine some rights in our Constitution or Bill of Rights. The people [have] to be educated and they [have] to practice their skepticism and their education, otherwise we don’t run the government, the government runs us.”

![Sagan shown in an interview with Charlie Rose months before Sagan's death. [Photo credit: PBS]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/deadstate-carl-sagan.png)

In his passionate popularization of science, Sagan inevitably clashed with pseudoscience and fundamentalist religion. This clash made him realize that the most important things to impart were not what we know, but the methods we used to arrive at knowledge. He writes in The Demon-Haunted World, “If we teach only the findings and products of science, no matter how useful and even inspiring they may be, without communicating its critical method, how can the average person possibly distinguish science from pseudoscience? Both then are present as unsupported assertions.” A few paragraphs forward, he writes, “It is a supreme challenge for the popularizer of science to make clear the actual, tortuous history of its great discoveries and the misapprehensions and occasional stubborn refusal by its practitioners to change course… It is enormously easier to present in an appealing way the wisdom distilled from centuries of patient and collective interrogation of nature than to detail the messy distillation apparatus. The methods of science, as stodgy and grumpy as they may seem, are far more important than the findings of science.”

But his brand of skepticism was not just directed toward charlatans, it was directed toward human frailty in general. “Perhaps the sharpest distinction between science and pseudoscience is that science has a far keener appreciation of human imperfections and fallibility than does pseudoscience, or inerrant revelation,” he noted. In the last interview with Charlie Rose he said, “Science is more than a body of knowledge. It’s a way of thinking, a way of skeptically interrogating the universe with a fine understanding of human fallibility.”

![[Photo credit: izquotes.com]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/quote-science-is-a-way-of-thinking-much-more-than-it-is-a-body-of-knowledge-its-goal-is-to-find-out-how-carl-sagan-320431.jpg)

The staying power of Sagan’s perspective rests on the fact that it was in equal measure all too human and completely cosmic. The key to this union of the grand and the humble, the timeless and the timely, can be found in the first episode of his world-famous PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, where he said, “The cosmos is also within us. We’re made of star-stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.” Sagan made no distinction between his passion for the universe and his love for humanity. To him, they were the same thing. This is why his message is still relevant to us today, and why his personal voyage still has a lot to teach us.

Have an enlightening Carl Sagan Day!

![[Photo credit: Skeptic Magazine]](https://filipinofreethinkers.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/10712714_10152755216082900_5397493461203212855_n.jpg)

And it is for this very reason that most of my accounts have a password that contains “stardust”, “universe” and “Sagan”.

To most, Carl Sagan is a renowned astronomer and scientist, an icon of pop culture even. But on a more personal note, he is a philosopher at par with the likes of Aristotle and Plato, only on a technical scale in the field of astronomy. Watching his Cosmos series has been a very humbling experience for me, as it gives me a sense of humanity’s “smallness” in the vast scheme of the universe, that our petty wars and economic tribulations are but a drop in the cosmic ocean, and that no one can save us from ourselves but us. His novel-turned-movie, Contact, which starred Jodi Foster, has changed my life in more ways than one. I remember watching that movie when I was 11 years old, and that probably sparked my interest in science, astronomy, philosophy, and consequently gave birth for my disdain of any religion that requires me to hate another human being. The sight of that wormhole… Jodi’s grand vision of the galaxies… Humanity’s insatiable quest for exploration… Carl Sagan nailed it.

Twenty years on since I first saw that movie, I am reminded that humanity’s troubles and heartaches, quarrels and vanities, are no more than a speck of dust, trapped on a pale blue dot that spins for a moment in time. Whether it is the billionaire cruising on his yacht in France, or a single mother paid $2/hr in the clothing factories of Bangladesh, I am reminded that Carl Sagan’s message applies to us all, that every atom in every body originated from the stars, and that racial divide or religious wars were borne from ignorance. I can go on all day on how Sagan has impacted my life, but it is my greatest wish that Filipinos, whose lives are utterly consumed by religious indoctrination, will break free from centuries of mysticism and myth, then start embracing scientific inquiry and reason as a tool to carve their own niche of glory in world history. We can’t possibly pride ourselves as domestic helpers and nurses abroad, can we?

Maybe it was too much of a rant on social media to accuse the big bosses of promoting stupidity, but how many of our local networks have actually shown Cosmos to the masses? Kahit e-tagalize man lang?

None.

And I have been ostracized for it.