When Christopher Hitchens died in December of last year, the atheist community echoed to the point of cliché that the world had lost a voice of reason. But, there was really no other way to put the loss of Hitchens. Hitchens was a prolific writer, with over a dozen published books, along with regular columns published on Vanity Fair, Slate, and The Atlantic. Even the toll of metastatic cancer could only do so much to diminish his output.

Hitchens died after over a year of battling esophageal cancer. Or rather, as he puts it, cancer fighting him. He wrote missives from the land he called Tumortown with the wit and vigor, however slowed by chemotherapy, that was unique to him. These dispatches were published in Vanity Fair, which comprise the bulk of Hitchens’ posthumously published book, Mortality.

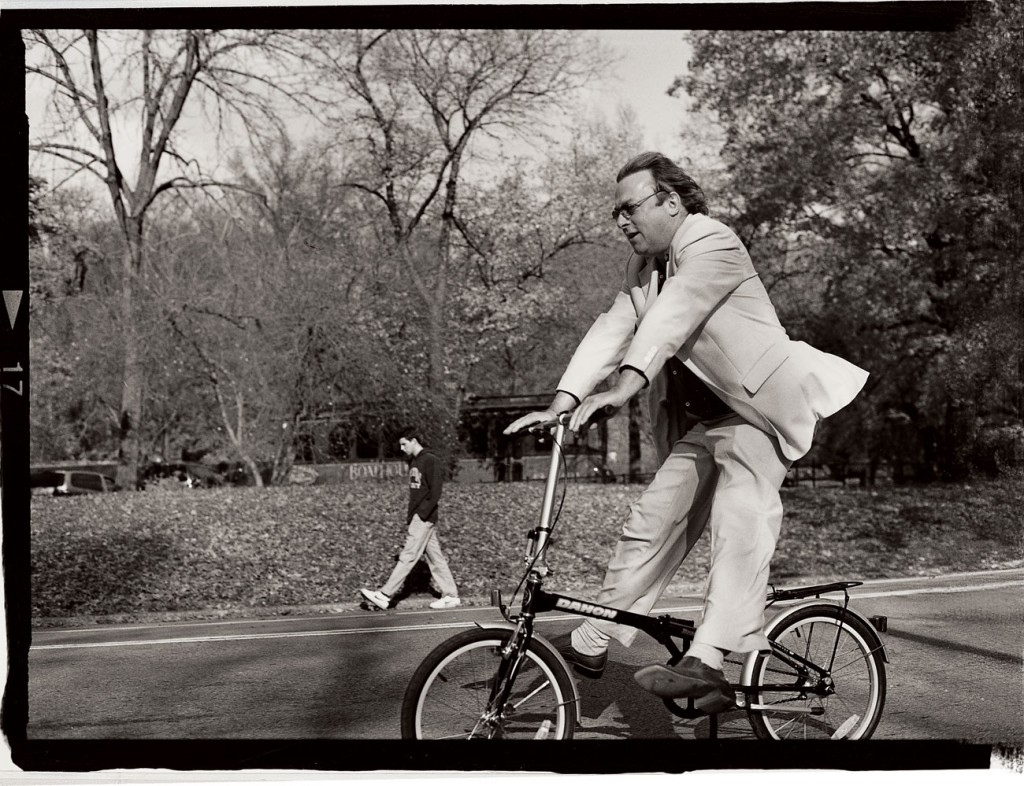

Mortality begins with a foreword from Hitchens’ longtime editor at Vanity Fair, Graydon Carter. Carter gives us a glimpse of Hitchens’ writing method as he recounts one typically indulgent drinking session, after which Hitchens banged out a 1000 word column “of near perfection” in about 30 minutes. He talks about the story behind the iconic photo of Hitchens riding a bike, feet in the air—apparently breaking one of the odd laws of New York. Carter remembers Hitchens as the consummate writer, taking on assignments however frightening (such as a date with the waxing parlor), while declaring with nervous enthusiasm, “In for a penny…”

The “living dyingly” by an atheist, of which Hitchens wrote in his final days, served as a real depiction and acceptance of mortality. After all, dying is no more real to anyone but atheists who believe that this life is all that there is and all that there will be. Hitchens, however, warned of the “permanent temptation” of self-centeredness and solipsism that stems from cancer victimhood and a looming end of life. As a matter of “etiquette,” Hitchens imposed on himself not to inflict on others the torment of indulgence expected from people dealing with the dying. He pointed out in particular the well-loved Randy Pausch, of The Last Lecture and Oprah fame. He remarked, “It ought to be an offense to be excruciating and unfunny in circumstances where your audience is almost morally obliged to enthuse.” Unflinching takedowns such as this remind us of the cheeky audacity that the world lost when Hitchens died.

Despite his near-stoic bravery as he journeyed through the land of malady, Hitchens admits that he would sometimes falter and throw the banal challenge to the universe of “why me?”, of course, Hitchens’ clear rationality sternly admonishes him with the obvious “why not?” Mortality shows how Hitchens maintained his humor despite the understandable irritation of the courtesies when interacting with people from “the country of the well.” When asked, “How are you?,” he would give different playful responses, from “A bit early to say” to “I seem to have cancer today.”

Most heartbreaking is how Hitchens relayed the eventual loss of his legendary voice, “If I had been robbed of my voice earlier, I doubt that I could have ever achieved so much on the page.” He related the vocal cord, which is not at all a cord in its strict sense, to the musical chord and how there must lie a deep relationship between the etymology and how the human voice evokes emotion. Speaking was at the core of Hitchens’ identity and he saw its loss as “assuredly to die more than a little.”

Hauntingly, Hitchens recalled the time when he was waterboarded in order to write about the experience, which he describes as being slowly drowned. It’s quite revealing for a dying man to have an action the United States government denied was torture in his last recollections. Having pneumonia as one of the many perils of his disease, Hitchens would have fits of panic with the feeling of water filling his lungs, summoning back his experience with torture.

Among the most memorable passages of Mortality was one of the first Hitchens published after being diagnosed. He spoke of his plans that were interrupted by cancer. Valiantly, he expressed his desire of outlasting the “elderly villains,” Kissinger and Ratzinger. But, Hitchens’ disappointment was clearest and most moving when he disbelievingly lamented, “Will I really not live to see my children married?”

The closing chapter of Mortality allows us a quick look at Hitchens’ thought processes before they were laid out in crisp British prose. We see little notes that echo some of the previous chapters, which were the fleshed out beats from what Hitchens had jotted down.

As a prominent atheist, many believers pined, even threatened, for his conversion. This theme recurred in his final public appearances, when he assured people that should he ever convert, “I hereby state that while I am still lucid that the entity thus humiliating itself would not in fact be ‘me.’” In the closing notes of Mortality, Hitchens elaborates in one fragmentary passage, “If ever I convert it’s because it’s better that a believer dies than an atheist does.” I would have loved to have seen that line bloom into a full polemic.

At just around 100 pages of previously-published material, Mortality leaves readers wanting. And, perhaps, that is just the hazard for people who have lived lives such as Hitchens. However, having all the material in one place provides a solemn context to Hitchens as he allowed the public to watch an atheist die and, as he saw it, cease to exist. Mortality encapsulates the resolute bravery of Hitchens in the face of death, refusing the comforting delusions of religion, as well as secular, but no less self-indulgent, sentimentality.

Hitchens’ widow, Carol Blue, closes the book with her own stories about her husband. She recalls how Hitchens scribbled notes in his books and how, even after Hitchens died, she would revisit them. And then Christopher Hitchens would always have the last word.

Mortality by Christopher Hitchens is published by Twelve.

Image Credit: Vanity Fair